THE DETERMINATION OF DAMAGE AND DAMAGE INDICES FOR REINFORCED CONCRETE BEAMS DESIGNED TO 1972 MINISTRY OF WORKS DESIGN CODES

By

Nicholas Gulley

James Bilkey

James Stewart

Ben Dare

Foreword

The work that needed to be undertaken during this project was too large to be completed by a single student for their forth year project. This has meant that this project has been completed by four students, James Bilkey (JB), Ben Dare (BD), Nicholas Gulley (NG) and James Stewart (JS) as part of a combined 4th year project. All of the work including the designing and building was completed as a group. Each individual conducted a quarter of the testing program that was required. The analysis of the laboratory data was undertaken using a range of spreadsheets developed as a group. Each person has written a section of the report along with writing up their own results. This is detailed in the table of contents with the author in brackets. This project was conducted under the supervision of Dr Barry Davidson.

Technical Abstract

Currently there is no prescribed method for determining the amount of damage sustained by a reinforced concrete structure designed to pre 1972 New Zealand design standards during an earthquake. One of the key features of these designs is the amount of shear damage that is observed and the lack of knowledge today, in assessing and repairing this form of damage. For the assessment of damage sustained by a structure during an earthquake it is necessary to establish a relationship between the observed damage and the actual remaining strength. A large number of damage indices have been prescribed by researchers throughout the world in an attempt to quantify a prediction of the state of damage a structure has sustained. Twelve different loading histories were applied to twelve nominally identical beams to categorise a quantitative method for the comparison of observed damage sustained with the remaining strength. It was established that there was a substantial difference between the calculated nominal shear strength and the actual strength obtained during testing. It was also established that no prescribed damage index was able to consistently predict the damage sustained during the testing stages. Four damage states have been prescribed to enable the categorisation of observed damage into various levels of damage. Criteria for identifying each damage state has also been developed from comparison of the test results.

Acknowledgements

There are many people that we would like to thank for assisting us in the construction, testing, analysis and report writing that was involved in completing our project.

Firstly, we would like to thank Dr. Barry Davidson for supervising this project and providing us with ever useful advice, which was greatly appreciated. We would also like to thank Les Megget for helping us with the technical aspects of our beam design. Thanks also to Hank Mooy, Tony Daligan and Mark Byrami for helping with the construction and testing.

We would like to thank Pacific Steel and Allied concrete for supplying the materials, without which this project would not have been completed.

Finally, we would like to thank all of our friends and family for supporting us during this project. Your support has helped us to complete this project on time and finish our degrees.

Table of Contents

2.0 Literature Review (NG) 2-1

2.1.1 Cumulative Ductility. 2-2

2.2 Roufaiel and Meyer (1987) 2-2

2.2.1 Comparison by Liddell (2000) 2-4

2.2.2 Comparison by Williams et al. (1997) 2-4

2.2.3 Comparison by Ghobarah et al. (1999) 2-5

2.3 Development of the Park and Ang Damage Index. 2-5

2.3.1 Comparison by Williams et al. (1997) 2-8

2.3.2 Comparison by Cosenza et al. (1993) 2-9

2.3.3 Comparison by Kunnath et al. (1997) 2-10

2.4 Banon and Veneziano Index. 2-12

2.5 Cosenza et al. (1993) Index. 2-12

2.6.1 Comparison by Liddell (2000) 2-13

2.6.2 Comparison by Williams and Sexsmith (1995) 2-14

2.7 Chung, Meyer and Shinozuka Damage Index. 2-14

2.8 Damage index by Kunnath et al. (1992) 2-17

3.1 Earthquake Reinforced Concrete Structures. 3-1

3.1.1 Current Performance Criteria. 3-1

3.1.2 Current Design Methodology for Ultimate Limits. 3-2

3.3 Measuring Observed Structural Damage. 3-6

3.4.1 Components of Displacement 3-6

3.4.1.1 Shear Displacement 3-7

3.4.1.2 Flexural Displacement 3-8

3.4.1.3 Rocking Displacement 3-9

3.4.1.4 Calculated Displacement 3-9

4.0 Test Assembly Design, Construction, and Set-Up (BD) 4-1

4.2.1 Design/Loadings Codes. 4-3

4.2.2.1 Longitudinal Reinforcement 4-5

4.3.1.1 Steel Reinforcement 4-8

4.3.2 Construction Sequence. 4-13

4.6 Separate Displacement Components. 4-19

5.0 Applied Loading Histories (JS) 5-1

5.1 International Standard Loading Histories. 5-1

5.1.1 Conventional approach from New Zealand. 5-1

5.1.2 Conventional approach from the Public Works Research Institute in Japan. 5-3

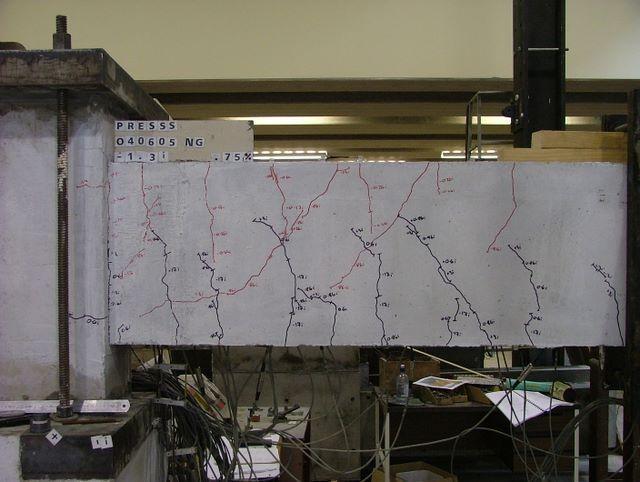

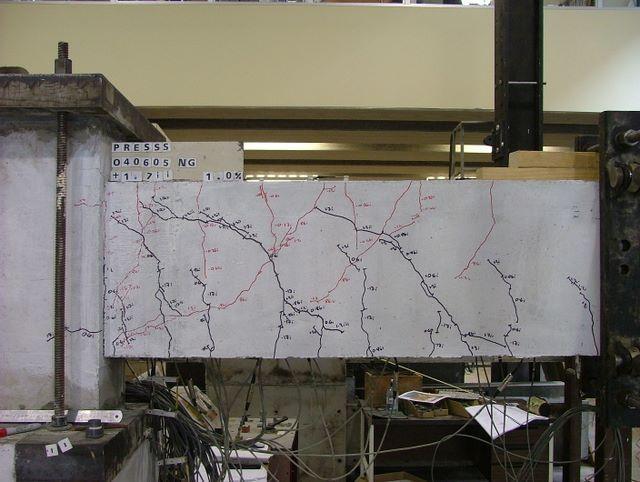

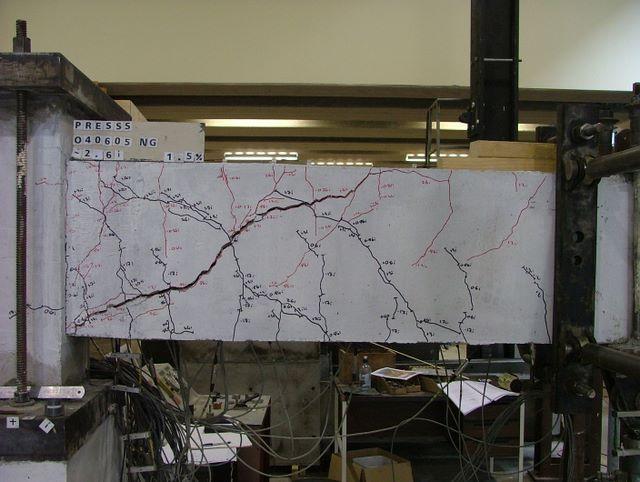

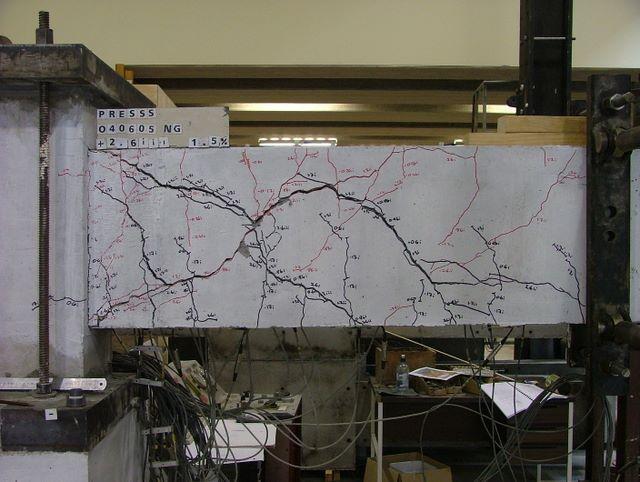

5.1.3 Conventional approach from the PRESSS Research Programme. 5-4

5.1.4 Conventional approach from the University of California at Berkley. 5-4

5.2 Fabricated Loading Histories. 5-5

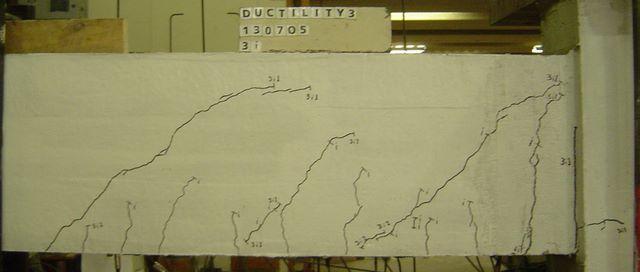

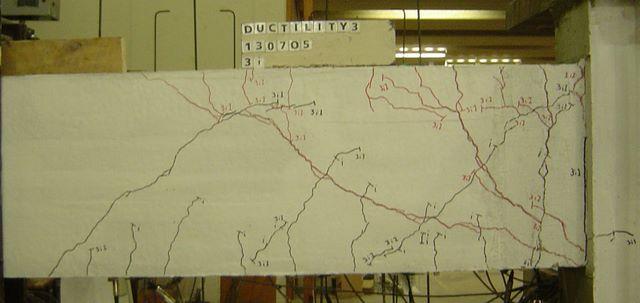

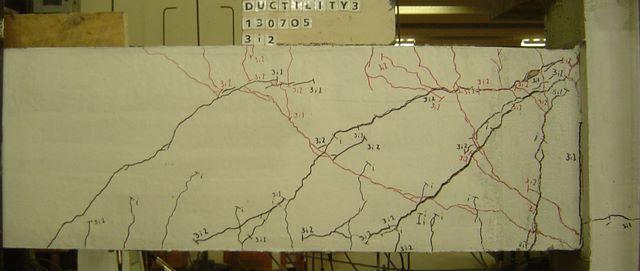

5.2.2 Bi-directional Cycling at Ductility 3. 5-6

5.2.3 Uni-directional Cycling. 5-7

5.3 Earthquake Loading Histories. 5-7

5.3.1 Earthquake Loading History A.. 5-8

5.3.2 Earthquake Loading History B.. 5-9

5.3.3 Earthquake Loading History C.. 5-9

5.3.4 Earthquake Loading History D.. 5-10

5.3.5 Earthquake Loading History E. 5-10

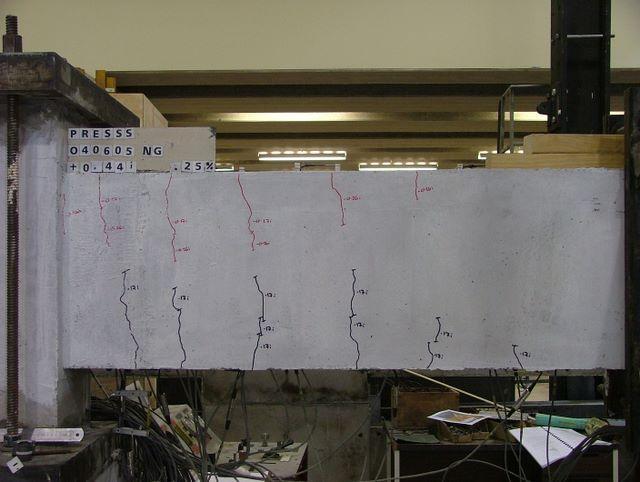

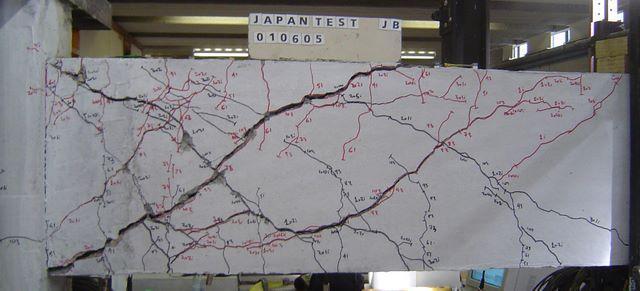

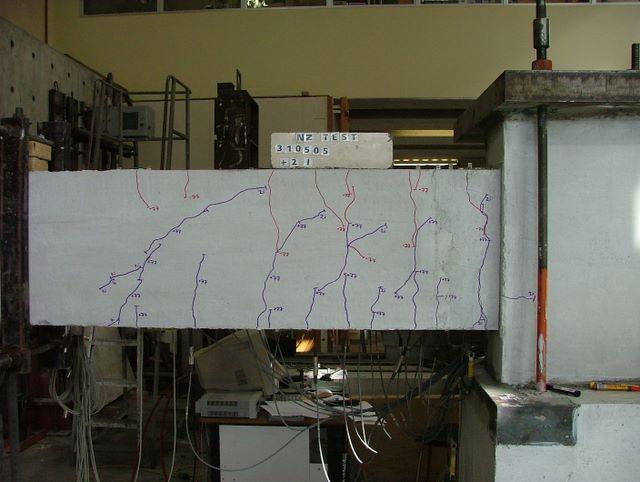

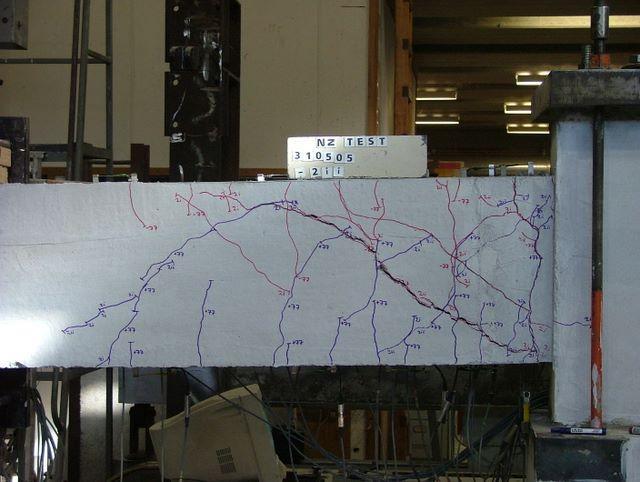

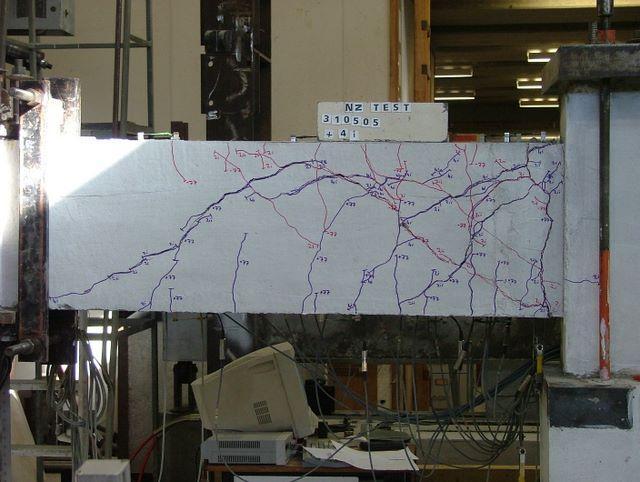

6.1 New Zealand Loading History (NG) 6-2

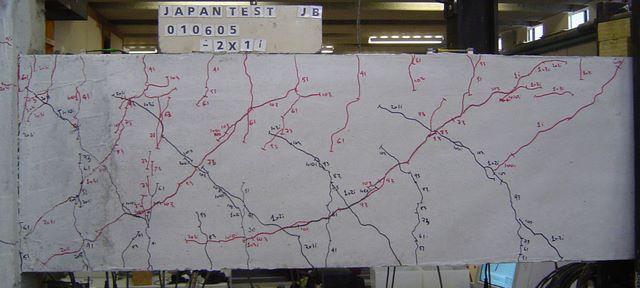

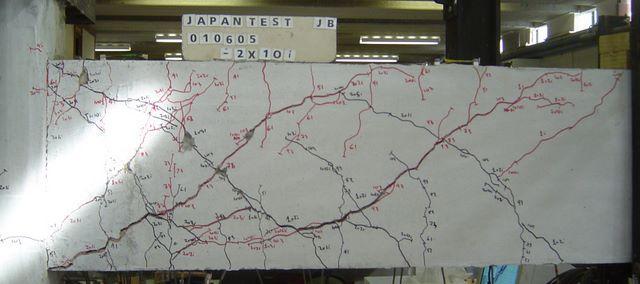

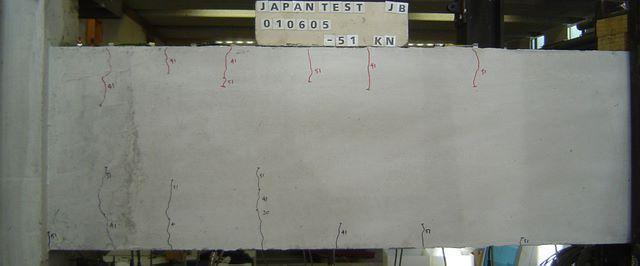

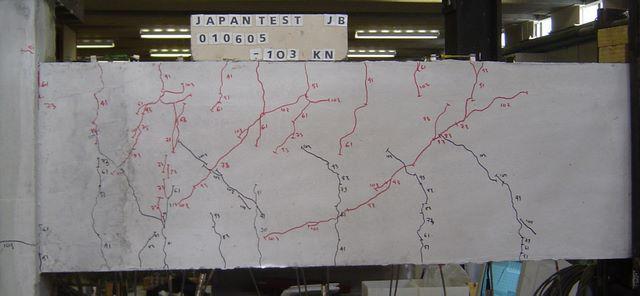

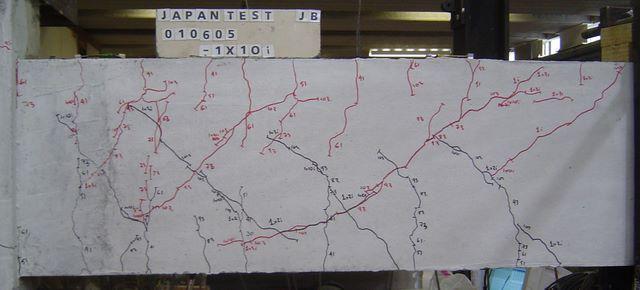

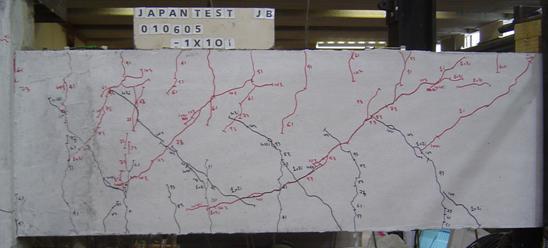

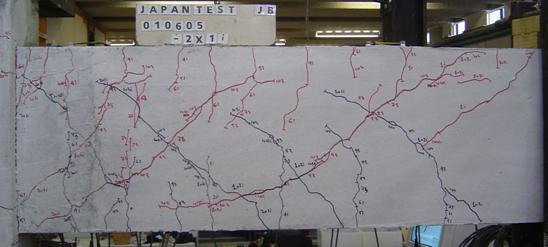

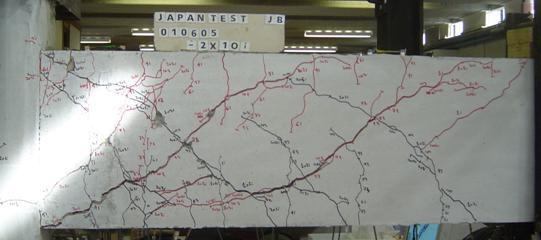

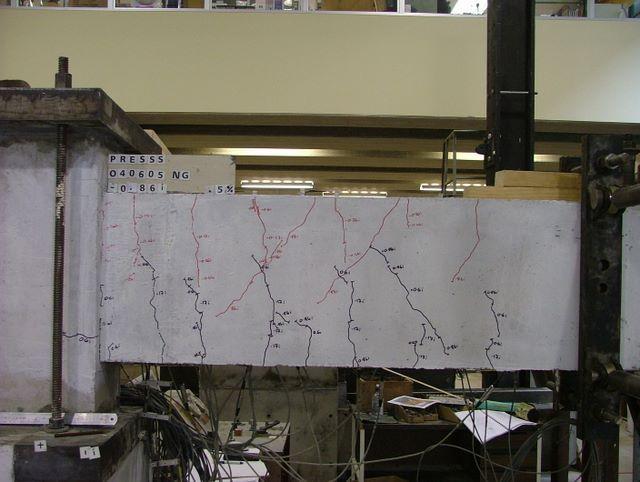

6.2 Public Works Research Institute (JB) 6-5

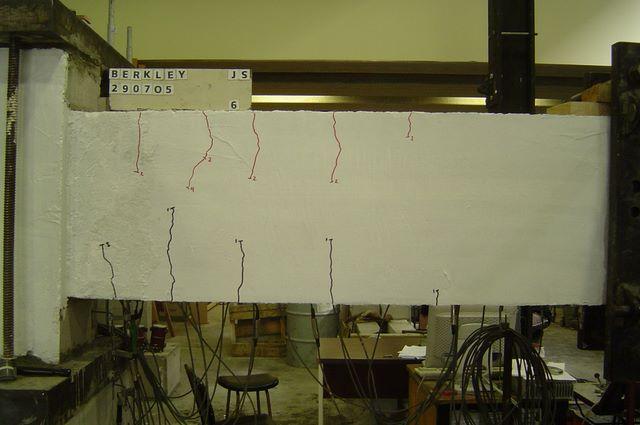

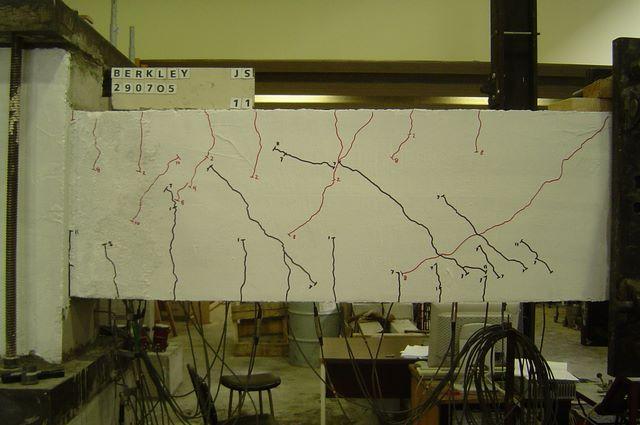

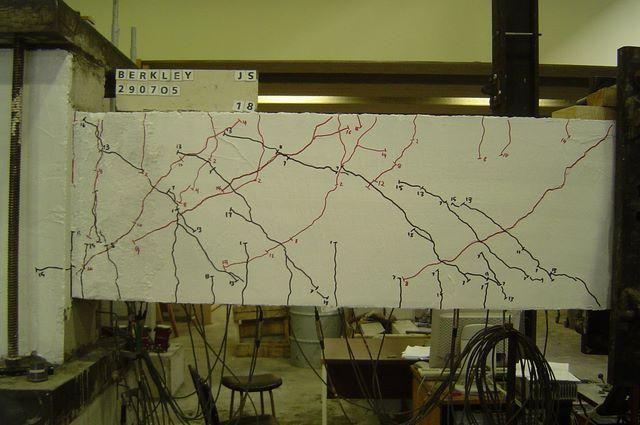

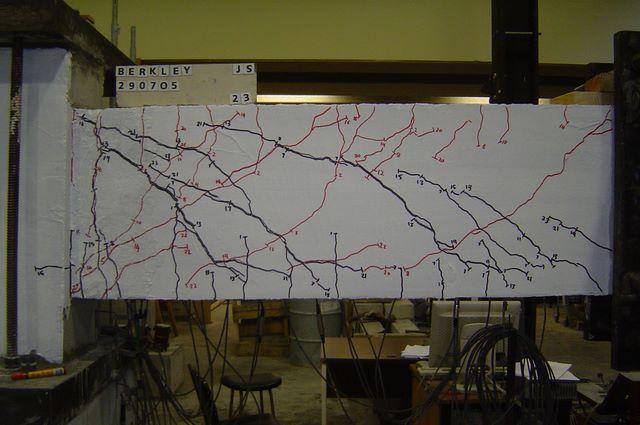

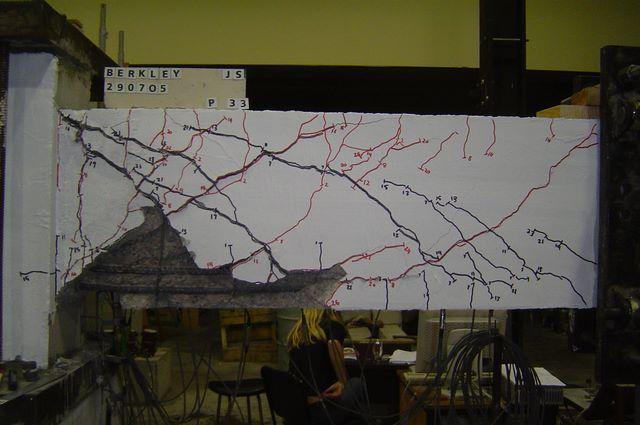

6.4 Berkeley Loading History (JS) 6-9

6.5 Monotonic Lading History (BD) 6-12

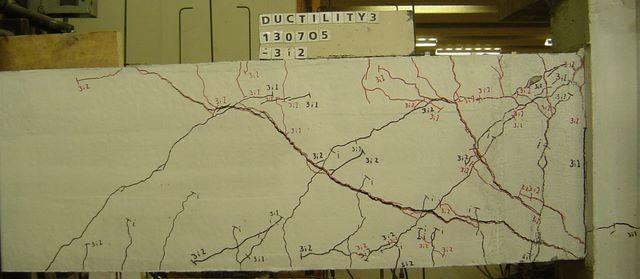

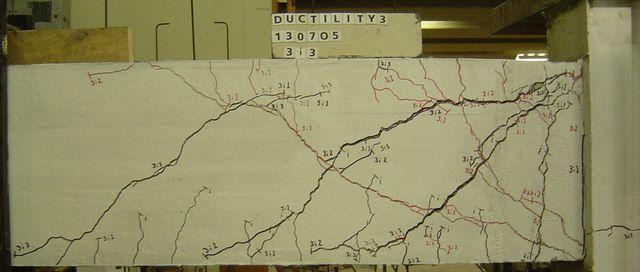

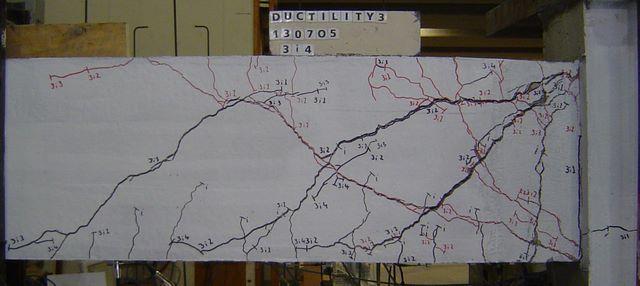

6.6 Bi-directional Cycling at Ductility 3 (JB) 6-15

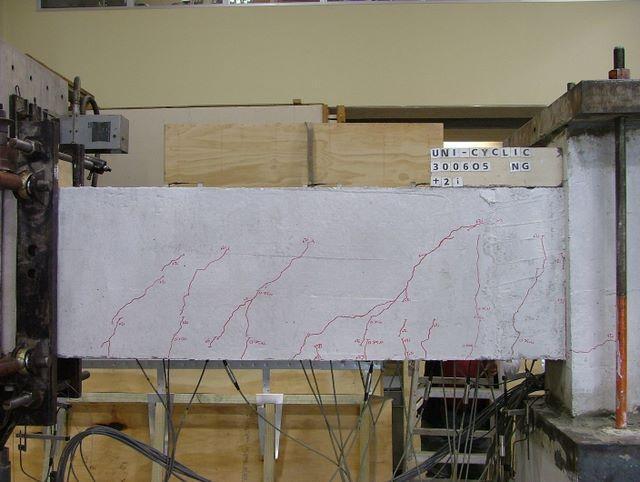

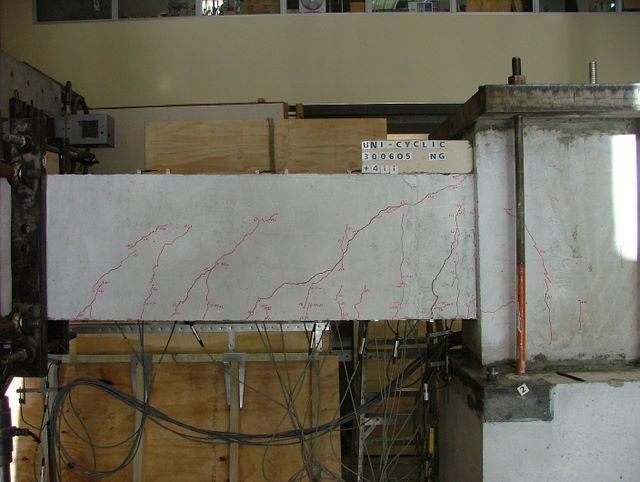

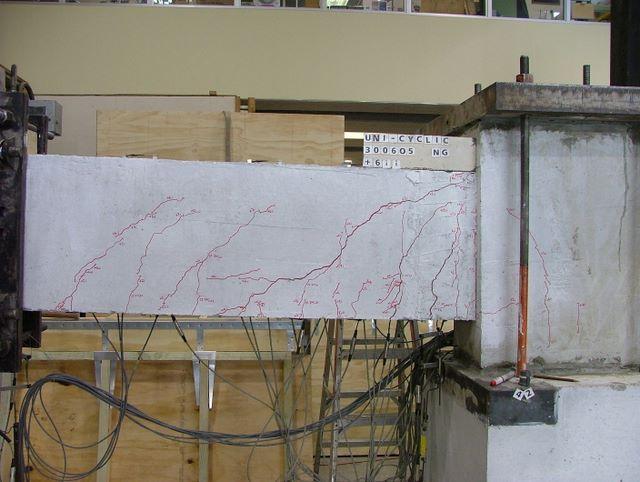

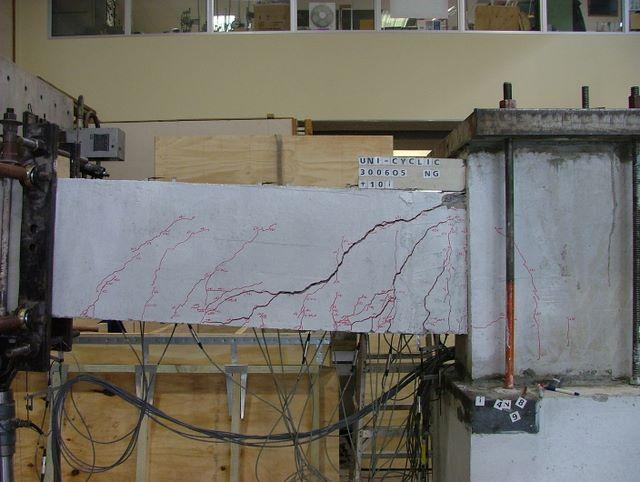

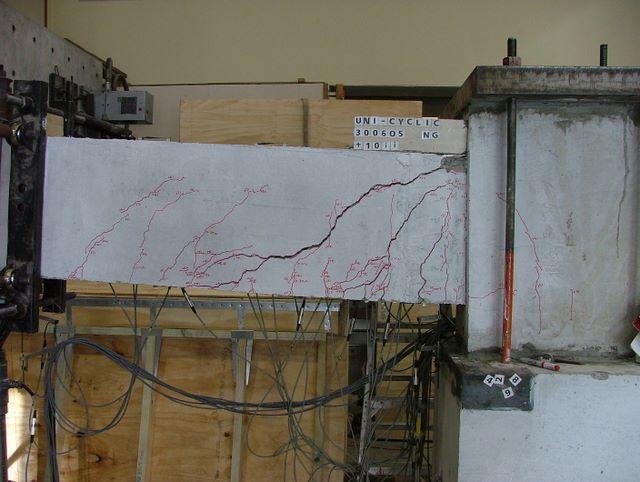

6.7 The Uni-directional Cycling Test (NG) 6-17

6.8 Earthquake Loading History A (BD) 6-19

6.9 Earthquake Loading History B (JB) 6-21

6.10 Earthquake Loading History C (BD) 6-23

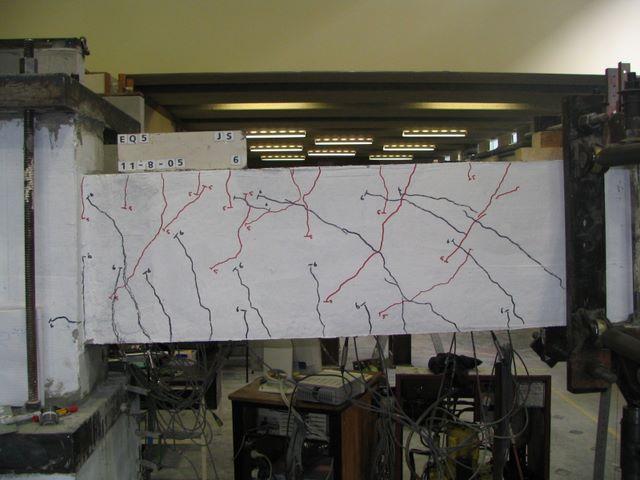

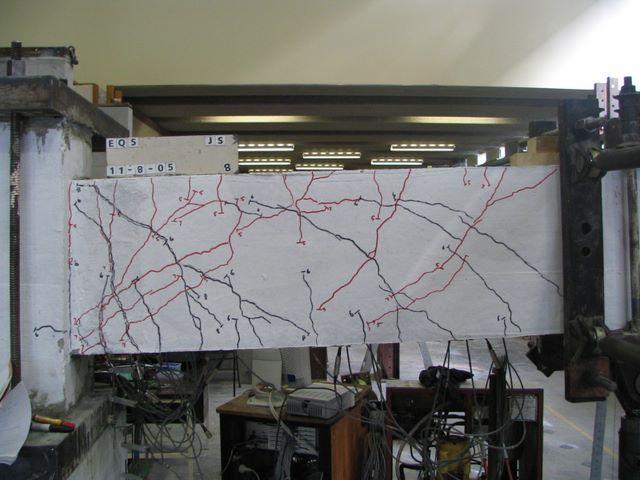

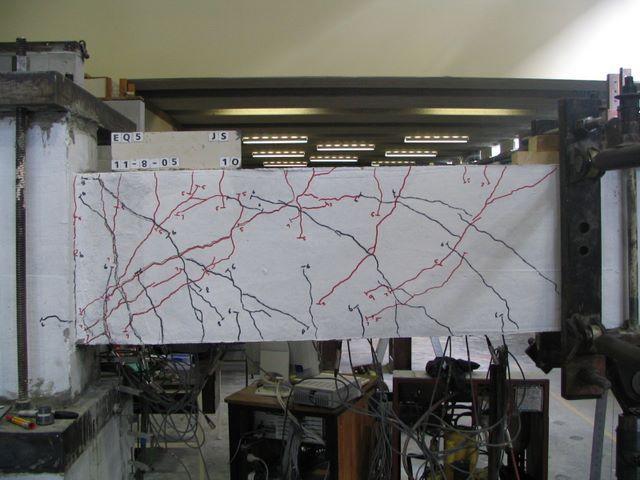

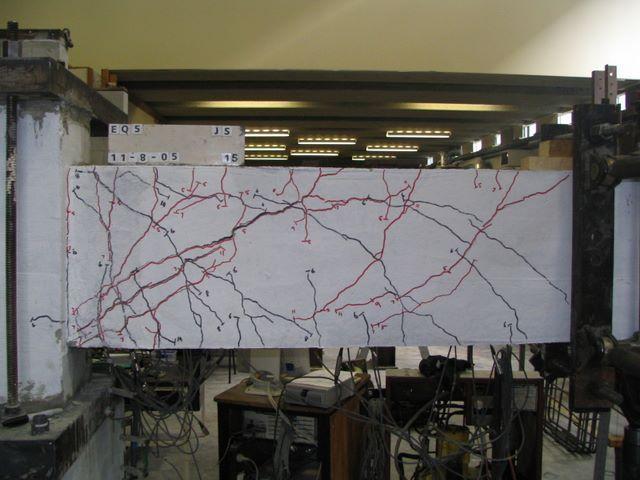

6.11 earthquake Loading History D (JS) 6-26

6.12 Earthquake loading History E (JS) 6-28

7.0 Comparison of Results (NG, JB, JS, BD) 7-1

7.1 Comparison of the Laboratory Loading Histories. 7-1

7.1.1 Failure Load and Displacement 7-2

7.2 Comparison between the Laboratory tests and the Earthquake Loading Histories. 7-3

7.2.1 Failure Load and Displacement 7-4

7.3 The Ability of Damage Indices to Reflect Failure. 7-5

7.3.5 Banon and Veneziano. 7-7

7.3.6 Summary of Damage Indices. 7-7

7.4 The Ability of the Damage Indices to Reflect Observed Damage. 7-7

7.5 Other Methods to Reflect Observed Damage. 7-7

8.0 Conclusions (NG, JB, JS, BD) 8-1

8.3 Comparison of results. 8-2

Appendix A: Results and Analysis. A-1

A-1 The New Zealand Loading History. A-2

A-2 Public Works Research Institute Loading History. A-8

A-3 The PRESSS Loading History Test A-14

A-4 The Berkeley Loading History Test A-20

A-6 Cycling at Ductility 3. A-33

A-7 The Uni-directional Cycling Loading History. A-39

A-9 Earthquake A Loading History. A-45

A-10 Acceleration B Loading History. A-52

A-11 Earthquake C Loading History. A-58

A-11 Acceleration History D.. A-65

A-12 Acceleration History E. A-71

List of Tables

Table 2-1: Park and Ang Damage Classification Levels (Singhal and Kiremidjian 1995). 2-7

Table 2-2 Bracci et al. Damage Classification Levels. 2-13

Table 2-4: Typical Range of Values for ß. 2-18

Table 2-5. Damage Condition and corresponding Limiting Damage Indices (Stone and Taylor, 1993) 2-19

Table 4-1 Concrete Mix Design for batch one. 4-12

Table 4-2 Concrete Mix Design for batch two. 4-12

Table 5-1 Summary of Earthquake Loading History Design Factors. 5-8

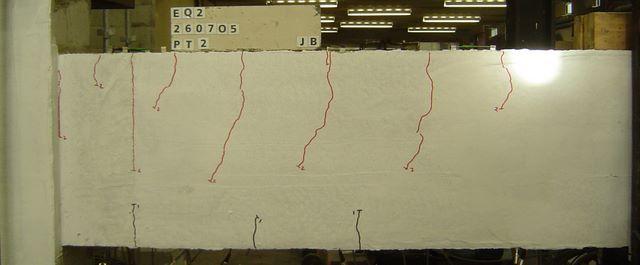

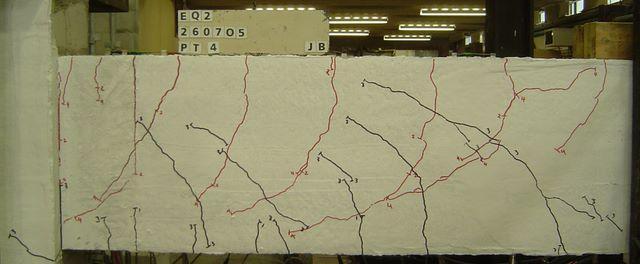

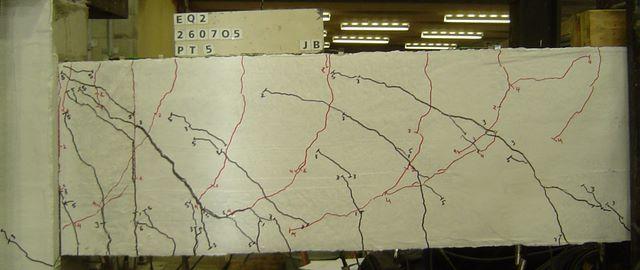

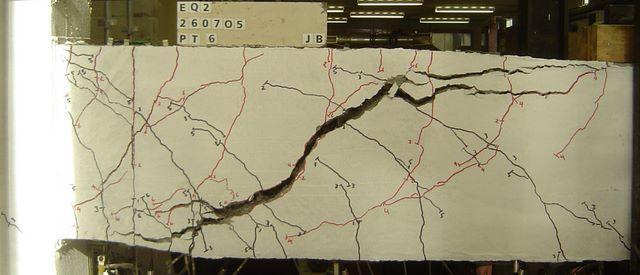

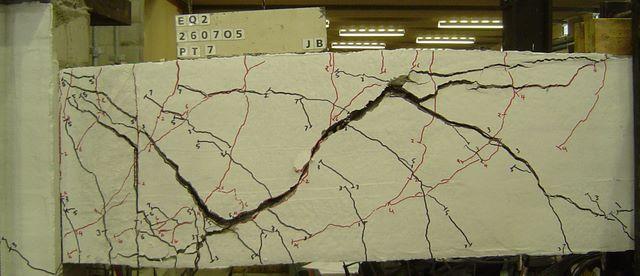

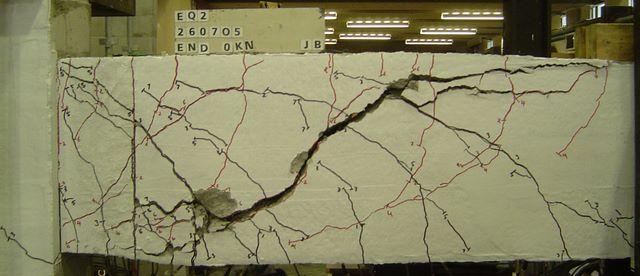

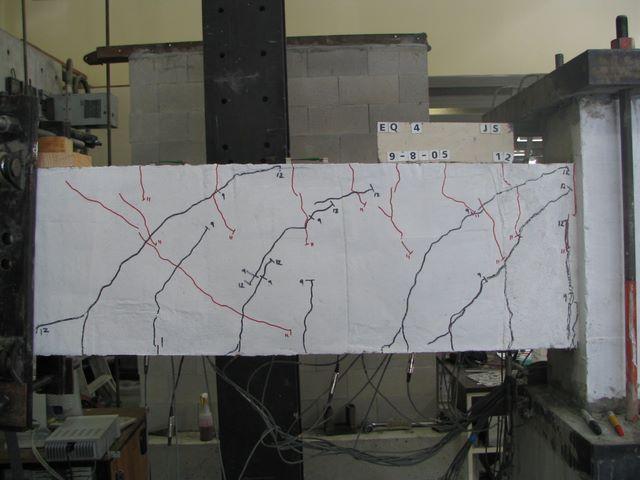

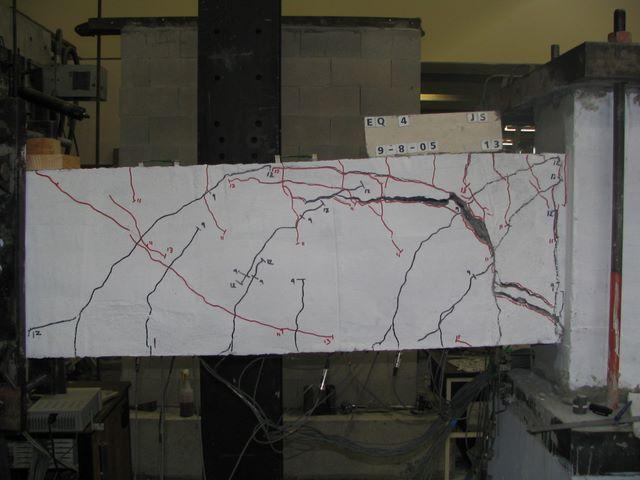

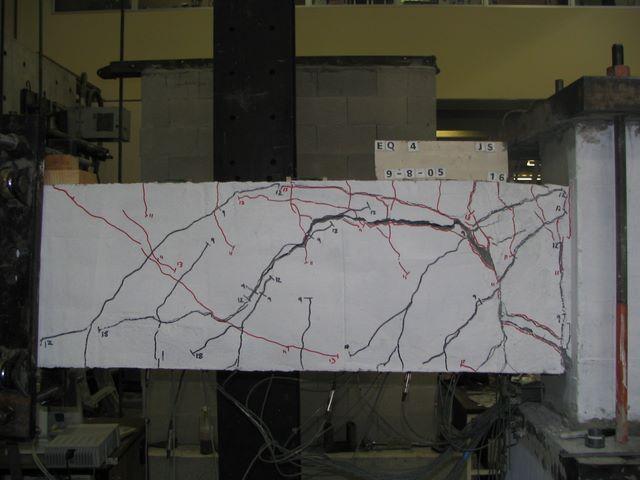

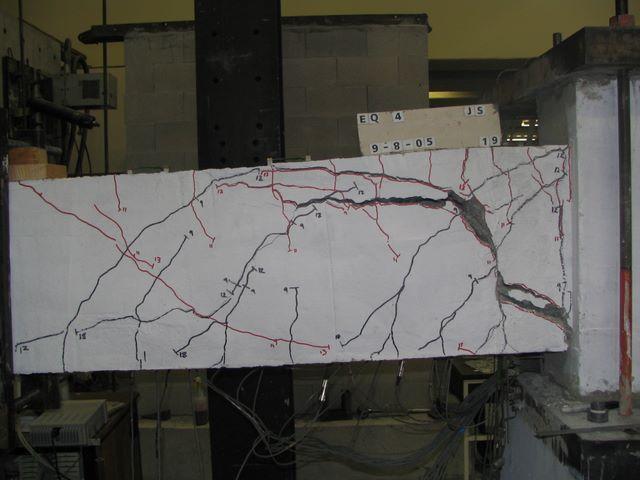

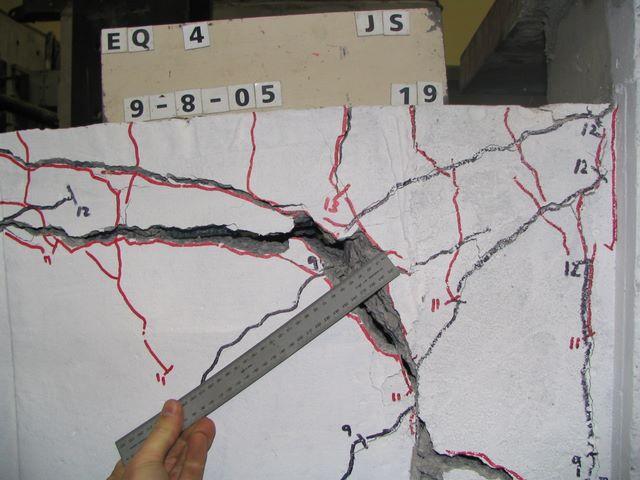

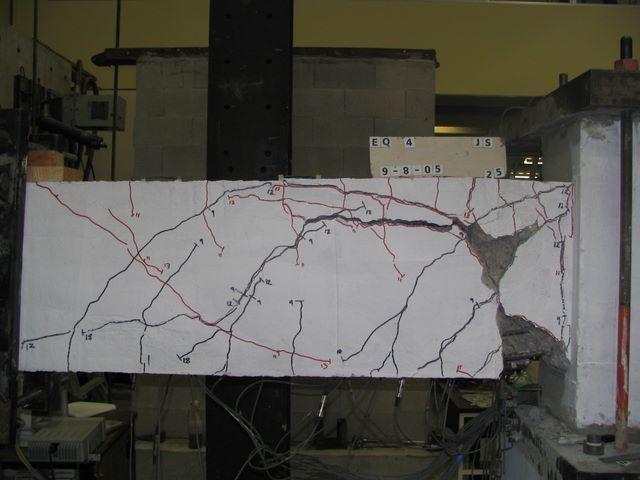

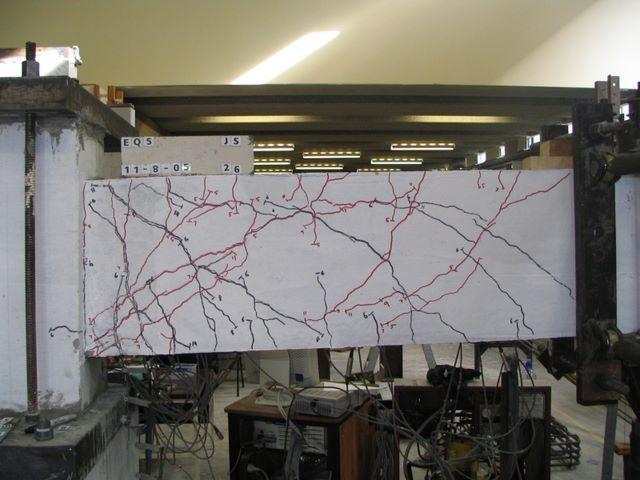

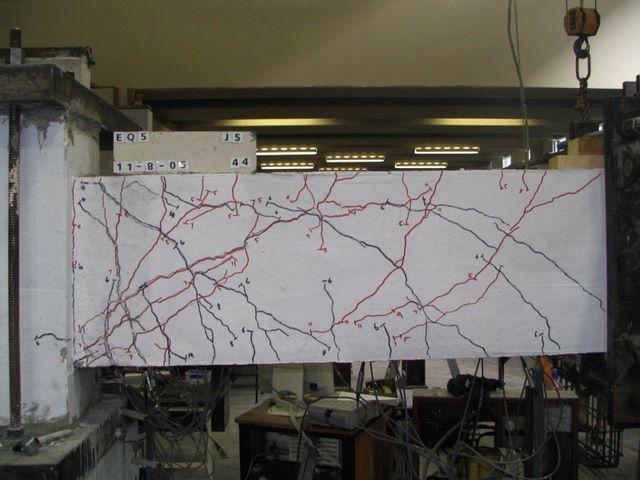

Table 7-1 Crack widths and Increase in Depth for Standard Laboratory Tests at Failure. 7-3

Table 7-2 Crack widths and Increase in Depth for Earthquake Loading History Tests at Failure. 7-5

Table 7-3 Criteria for damage states. 7-9

List of Symbols

+ Positive or an up load cycle

- Negative or an down load cycle

a Calibration factor, usually 1.1

b Calibration factor, usually 0.38

![]() Strength damage

Strength damage

![]() Damage potential

Damage potential

![]() Deformation damage

Deformation damage

![]() Distance between the centre of this gauge group and the centre of the actuator

Distance between the centre of this gauge group and the centre of the actuator

dE Incremental dissipated hysteretic energy.

Ec(d) Hysteretic energy per loading cycle at deformation equal to, d.

Eh Dissipated energy

ET Dissipated hysteretic energy

![]() Elongation of gauge group

Elongation of gauge group

Fy Yield strength

![]() Height of gauge panel

Height of gauge panel

I Indicator of different displacement or curvature levels

J Indicator of cycle number for a given load level i

l/d Shear span ratio (taken as 1.7 if l/d < 1.7).

Mm Moment capacity of a section associated with the failure strain em

Mult Maximum moment recorded under monotonic loading

Mx Moment as the test progresses

My Yield moment

![]() : number of cycles (with curvature level i) to cause failure

: number of cycles (with curvature level i) to cause failure

n0 Normalized axial stress (taken as 0.2 if n0 < 0.2).

nij Number of cycles (with curvature level i) actually applied

pt Longitudinal steel ratio, as a percentage (taken as 0.75% if pt < 0.75%).

?w Confinement ratio.

Qy Calculated yield strength (Qy is replaced by the maximum strength, Qu, if Qu is smaller than Qy).

![]() Elastic Horizontal Inertia Force

Elastic Horizontal Inertia Force

![]() Ductile Horizontal Inertia Force

Ductile Horizontal Inertia Force

![]() Width of gauge panel

Width of gauge panel

aij Damage accelerator

ß Non-dimensional, non-negative parameters to take into account the effect of cyclic loading. (for Park and Ang)

ß Strength degrading parameter (for Kunnath et al.)

![]() Flexural Displacement

Flexural Displacement

![]() Rocking Displacement

Rocking Displacement

![]() Shear Displacement

Shear Displacement

![]() Ultimate Horizontal Displacement

Ultimate Horizontal Displacement

dbBond slippage deformation

deElastic shear deformation

dfFlexural deformation

dmax Maximum deformation experienced during loading.

dsInelastic shear deformation

du Ultimate deformation experienced under monotonic loading.

dyYield deformation

![]() Curvature

Curvature

Øm Curvature associated with the moment Mm

Ømax Curvature associated with the maximum recorded moment from testing

Øult Curvature associated with the maximum moment measured during monotonic loading

Øx Curvature associated with Mx

Øy Curvature associated with the yield moment

µu Amplifying ductility factor

µ Ductility

![]() Gauge group angle

Gauge group angle

?m Maximum rotation attained during loading history

?r Recoverable rotation at unloading

?u Ultimate rotation capacity of the section

![]() Rotation of gauge group

Rotation of gauge group

1.0 Introduction (JS)

When a structure experiences a severe earthquake the damage caused to the structure depends on the magnitude and direction of the ground excitation and the dynamic and nonlinear characteristics of the structure. The standard of design and construction will then have a direct relation to the damaged and remaining available strength of a structure after an earthquake. Due to the extent of advancement in knowledge of structural engineering, standard codes are regularly updated, allowing the design of more reliable structures which will in turn perform better than an older designed structure in a similar earthquake. Therefore the prediction of damage and available strength from visual defects of a structure designed to a more recent standard is becoming increasingly separated from that of a structure designed according to an older standard.

To overcome this problem, researchers have developed damage indices as a quantitative way of measuring the damage sustained by a structural member during an earthquake. This way of quantifying damage can be applied to any structure no mater what the design and gives an acceptable level of damage generally ranging from undamaged to irreparable.

In New Zealand today there are many buildings that have been designed and constructed under the Ministry of Works design code (1970), many being government buildings or public buildings constructed under government funding. Therefore the cities of New Zealand comprise of a large proportion of structures that have been designed with the limited structural engineering knowledge of pre 1972.

This report is the combined work of Nicholas Gulley, Ben Dare, James Bilkey and James Stewart and attempts to quantify a comparison between damage indices, actual damage and observed damage. The results herein aim to aid the designation of a damage index based on visual defects such as crack width and orientation observed of the beams of a particular structure subjected to an earthquake. A scaled structural member was designed according to the 1970 Ministry of Works design codes to resemble a typical member from a three story structure. Twelve identical members were then subjected to a range of standard tests and displacement sequences that would be experienced due to an earthquakes impact on a three story structure. Performance of the members was calculated using five different damage indices and compared against observed damage during testing.

Section 2.0 of this report describes a number of common damage indices used throughout the world and gives a comprehensive review of previous studies that have attempted to compare or modify these different damages indices. Section 3.0 gives the theory behind this project. A description of earthquake reinforced structures, failure mechanisms, measuring observed structural damage and data processing. Section 4.0 details the design and construction of the test unit as well as the details regarding the test set-up and instrumentation. Section 5.0 summarises the seven different standard loading history tests and the five earthquake loadings histories applied during the experimental stage of this project. Section 6.0 states the results of the twelve different tests, including the comparison of the members’ performance with the calculated damage indices and observed damage. Section 7.0 presents a comparison of results detailed in Section 6. Lastly, Section 8.0 details the conclusions of this report.

2.0 Literature Review (NG)

A literature review into different damage indices was conducted as part of this report. A damage index is usually defined as the damage value normalised with respect to the (arbitrarily defined) failure level so that a damage index value of unity corresponds to failure (Chung et al. 1989). Damage indices attempt to numerically quantify the damage that has been sustained by a beam during an earthquake. Large amounts of research has been undertaken to validate and compare the different damage indices, this research is also reviewed for each of the different damage indices.

Damage indices have been formed to take into account different components of structural degradation and with varying degrees of complexity. There are cumulative and non-cumulative indices, deformation and energy based indices as well as damage indices that combine different components. The different damage indices that are investigated are Ductility in Section 2.1, Roufaiel and Meyer in Section 2.2, Park and Ang in Section 2.3, Cosenza et al. in Section 2.4, Bracci et al. in Section 2.5, Banon and Veneziano in Section 2.6. Two further damage indices by Chung et al. and Kunnath et al. are discussed in Sections 2.7 and 2.8 respectively. Research into the comparisons are conducted for Roufaiel and Meyer, Park and Ang and Cosenza et al. in their respective Sections.

2.1 Ductility Ratio (µ)

This is the most simple damage index and because of its simplicity is quite widely used. It is defined as the ratio of maximum displacement achieved to the yield displacement (Liddell 2000). Mathematically that is:

![]() Equation 2.1

Equation 2.1

A value for µ1 corresponds to the beam yielding and µ2 is 2xµ1.

2.1.1 Cumulative Ductility

Is the sum of all of the cyclic non-linear ductility’s that member has been subjected to. Researches such as Banon and Veneziano (1982) and Bracci et al. (1989) have used it in the formation of their damage indices. It can however be used as a damage index by itself.

2.2 Roufaiel and Meyer (1987)

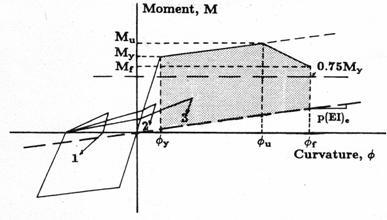

The damage index proposed by Roufaiel and Meyer (1987) is based upon a reduction in secant stiffness (Liddell 2000). They proposed a modified flexural damage ratio (MFDR) (Roufaiel and Meyer 1987) that took into account the direction of loading. The formula for the MFDR is shown below and the definition of each of the terms is shown in figure 2-1 and 2-2 and can also be expressed in terms of stiffness.

Equation 2.2

Equation 2.2

Equation 2.3

Equation 2.3

The MFDR is taken as the maximum of MFDR+ and MFDR-. A MFDR value of less than or equal to zero means that the member is undamaged, whilst a MFDR value of one signals the onset of failure.

Figure 2-1. Definition of Modified Flexural Damage Ratio (Roufaiel and Meyer 1987)

Figure 2-2. Moment curvature response from the New Zealand test showing the appropriate curvature values to use

The damage index was derived analytically and then a number of experiments were conducted to check the validity of the index (Roufaiel and Meyer 1987). This damage index accounts for the finite size of the plastic region and is appropriate to use when there is high shear or high axial forces. The results from the testing program have shown that the damage index created is a good indicator of the actual damage that has occurred to the beam (Roufaiel and Meyer 1987).

A number of tests have been undertaken using Roufaiel and Meyer’s damage index. Liddell (2000), Williams et al. (1997) and Ghobarah et al. (1999) have all conducted research using this damage index and are discussed in Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2 and Section 2.2.3 respectively. Chung et al. (1987) briefly mention Roufaiel and Meyer’s damage index in developing their own damage index.

2.2.1 Comparison by Liddell (2000)

Twelve tests were conducted on identical reinforced beams each having a different loading history applied to it, (Liddell 2000) four standard loading histories, five analytical acceleration histories and three fabricated tests. A number of different damage indices are investigated and the damage index proposed by Park and Ang (1985) is the most correct index (Liddell 2000). In the majority of the tests undertaken the value returned by the MFDR at the failure point was about 0.5 but was as low as 0.29 and as high as 1.25. A value of 1 or more only occurred in two tests, the Monotonic and Unidirectional Loading (Liddell 2000). Failure was expected in these two tests as the ultimate variables in the damage indices were normalised with respect to this test and both had the same ultimate ductility (Liddell 2000). In all of the other tests the index suggested that the beam had more strength available before failure would occur.

2.2.2 Comparison by Williams et al. (1997)

Six different tests were undertaken, each beam having a different moment to shear ratio or different stirrup spacing (Williams et al. 1997). All but one test recorded a MFDR value that was within 20% of a failure value. The MFDR values that were recorded when the test was stopped ranged from 0.9 to 3. The number of cycles and the shape of the curve for the different tests varied considerably. Williams et al. noted that most of the available damage indices consider flexural yielding only and do not consider the possibility of shear failure. The Roufaiel and Meyer index is described as being one of the best damage indices for the damage that has occurred to the beams (Williams et al. 1997). The overall conclusion from the paper by Williams et al. is that the “more sophisticated indices which attempt to take into account the damage caused by repeated cycling gives no more reliable an indication of damage than simple measures such as ductility and stiffness degradation”.

2.2.3 Comparison by Ghobarah et al. (1999)

Ghobarah et al. propose a new damage index and compare it with the damage indices proposed by Park and Ang (1985), Roufaiel and Meyer (1987) and the DiPasquale and Cakmak (1988) final softening damage model. The research is conducted on a three story frame building with four bays on one side and three on the other. They do this by comparing the damage indices at different peak ground acceleration and different levels of interstorey drift for different earthquakes. The research was not investigating whether failure occurred at the appropriate damage index, but whether there were any errors in the index and how they could improve their new index. Ghobarah et al. concluded that in some cases the averaging procedures that are employed by Park and Ang and Roufaiel and Meyer may give incorrect results.

2.3 Development of the Park and Ang Damage Index

The damage index proposed by Park and Ang (1985) is generally considered to be the most extensively used in technical literature. The development of the model was based on a linear combination of a simple ductility term, the maximum displacement, and the absorbed hysteretic energy (dissipated plastic energy). It was devised by investigating extensive test data taken from a variety of monotonic and cyclic loading sequences on reinforced concrete beams and columns, sourced in the U.S.A. and Japan (Park and Ang, 1985) the results of which were used to undertake a systematic regression analysis. All of the test sequences utilised single axis bending and were carried out on concrete members of rectangular section reinforced with deformed bars. The Park and Ang damage index is represented by the following models:

![]() Equation 2.4

Equation 2.4

or alternatively,

![]() Equation 2.5

Equation 2.5

The deformation terms, dmax & du can be determined directly from the stress-strain relationship of the structure when basic flexural behaviour is assumed, however when brittle failure modes are a possibility several additional factors need to be taken into consideration. Consequently an alternative solution was derived from an empirical relationship taken from monotonic test data taking into account the cumulative contributions of deformation resulting from flexure, shear, bond slippage, and elastic response. Following on from this the ultimate deformation can be represented by:

![]() Equation 2.6

Equation 2.6

Where ![]() Equation 2.7

Equation 2.7

In a similar fashion ß is based on the absorbed hysteretic energy results taken from selected test data, see Figures 2-3 & 2-4, which are integrated up to the point of failure, for members displaying brittle failure under cyclic loading. From this the following relationships were produced:

for Eq. 2.4: ![]() Equation 2.8

Equation 2.8

for Eq. 2.5: ![]() Equation 2.9

Equation 2.9

Of the above proposed equations (Eqs. 2.4 and 2.5) the first is by far the most widely adopted and is used in the bulk of comparative studies in which the model features, Eq. 2.5 is slightly more complicated as it takes into account the variation in the cyclic effect at different levels of deformation whereas Eq. 2.4 makes the assumption that the effect remains constant for all levels of deformation.

The levels of damage classification for the Park and Ang index suggested by Gunturi (1992) for various ranges of damage index were based on observations made on nine reinforced concrete structures which were affected by the 1971 San Fernando earthquake, the results of which are summarised in

Table 2-1. With reference to the aforementioned table, irreparable damage is described as crushing of the concrete and exposure of the reinforcement, repairable damage as severe cracking and localised spalling, and minor damage as light cracking.

|

Damage State |

Range of Index |

|

0.0 = D < 0.2 |

Minor Damage |

|

0.2 = D < 0.4 |

Repairable Damage |

|

0.4 = D < 1.0 |

Irreparable Damage |

|

D = 1.0 |

Collapse |

Table 2-1: Park and Ang Damage Classification Levels (Singhal and Kiremidjian 1995).

Although the Park and Ang model is widely accepted and applied throughout the world the two main assumptions upon which it is based have been disputed. Experimental evidence suggests that the assumption of the damage being a linear combination of the deformation and the absorbed hysteretic energy (Eqs. 2.4 and 2.5) and the manner in which the ß-factor considers several important structural parameters were not entirely valid (Chung et al. 1989). It should also be noted that under elastic response the results from Eqs. 2.4 and 2.5 should theoretically be equal to zero, but testing shows that they will return negligibly small nonzero D terms within the elastic range. This behaviour can be attributed to the fact that neither Eqs. 2.4 or 2.5 are normalised.

Since the first proposal and publication of the above damage index in 1985 there has been several alterations and adaptations to its original format, in response partially to this criticism and also due to non-critical improvements that have been made. Several of these variations are shown in the comparative studies detailed in Sections 2.3.1 to 2.3.4.

2.3.1 Comparison by Williams et al. (1997)

Williams et al. also used the damage index formulated by Park and Ang. They concluded that the results of all the damage indices had a tendency to display considerable scatter, which identified that none of the indices showed any real shear dependent behaviour. It was evident that the damage sustained during the testing was largely independent of the number of cycles and primarily was attributable to the level of deformation. From this they stated that deformation based indices were the most reliable. In addition to this the Park and Ang index was deemed to perform favourably during tests with large displacement cycles, dominant shear behaviour, and especially where ductile response was present.

2.3.2 Comparison by Cosenza et al. (1993)

Cosenza et al. addressed the issue of the need for the identification of a universal and precise definition of structural failure in reinforced concrete members under cyclic loading conditions. To produce such a general definition it was first necessary to establish a series of damage parameters with relevance to inelastic deformation and strength of structures subjected to repeated cyclic loading sequences.

This was attempted by comparing the results of several damage indices using both experimental loading histories and those experienced in previous real earthquakes. The main comparisons drawn were based on the damage model of Banon and Veneziano (1982). The basic ductility and dissipated hysteresis energy models were used as a basis to compare the more advanced indices mentioned above, using ten simple cyclic loading histories and four actual seismic events.

Throughout the study an attempt was made to calibrate the three main models in an effort to normalise them to produce a more representative comparison. This was done by finding mean values of the major defining parameters for each of the models, (a) for Banon and Veneziano, (b) for Park and Ang, and (b) for the Plastic Fatigue model.

Following these experimental and observed results Cosenza et al. (1993) were able to draw several relevant conclusions. It was seen that the Banon and Veneziano (1982) and Park and Ang damage indices provide conservative results compared with the plastic fatigue model when subjected to loading sequences consisting of a high number of cycles and minimal displacement. Also noted was the fact that the difference in results between Banon and Veneziano and Park and Ang were irrelevant when considering the simple cyclic histories analysed, while the plastic fatigue results were significantly different. However with the load sequences closely resembling that of the actual quakes the results for all were very similar.

2.3.3 Comparison by Kunnath et al. (1997)

Kunnath et al.(1997) conducted a comprehensive study in an attempt to determine the response of circular reinforced concrete bridge piers under repeated cyclic loading. The study was conducted in an effort to investigate the likely behaviour of such structures when subjected to actual earthquake loadings, similar to those experienced in the 1971 San Fernando quake, and in particular the cumulative damage that they could endure. In accordance to current AASHTO (American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials) specifications under flexural response twelve identical pier structures were designed and built to quarter scale at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland and prepared for testing.

Four separate damage indices were selected for evaluation during the research procedure in an effort to have a broad representation and also to make known the strengths and weaknesses of each index when used in conjunction with circular reinforced concrete sections.

They proposed that the success of a damage model should not entirely be dependent on its ability to accurately predict damage within a structural component prior to loading, although this is an essential function of any model. Models are also required to be able to be evaluated in such a manner that they can be successfully implemented to assess the structural integrity of a member following a seismic event. The testing of the twelve specimens was separated into two sections; the first six were subjected to a series of cyclic loading histories of varying amplitude and frequency while maintaining a set pattern. In contrast to this the final six specimens were tested using a series of random cyclic reversals, similar to what one would expect to experience during an actual seismic event.

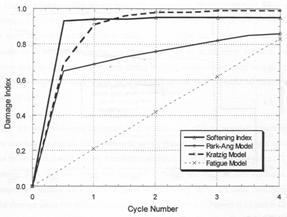

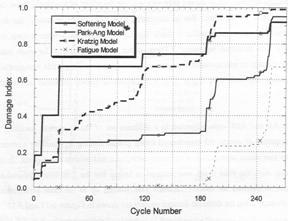

Figure 2-5. Comparative damage evaluation for specimen under lateral drift cyclic loading. (Kunnath et al. 1997)

Figure 2-6. Comparative damage evaluation for specimen under simulated major earthquake followed by two smaller after shocks. (Kunnath et al. 1997)

Under the more regular loading sequences of the first six specimens and especially during those tests with a large number of cycles and a low to medium level of lateral drift, up to 5%, the Kratzig et al. (1989) and softening index models demonstrated damage accumulation which was inconsistent with observed results. The models based on non-fatigue concepts, Kratzig et al. (1989), softening index, and Park and Ang, failed to accurately predict the damage state at the conclusion of the testing. When the specimens experienced a higher lateral drift and hence a lower number of cycles before failure the Park and Ang index was seen to perform better when the actual displacement exceeded the yield displacement. All of the non-fatigue models over-predicted the initial damage resulting from the first cycles and demonstrated their inability to cope with low-cycle fatigue damage, this is evident in Figure 2-5. The non-fatigue models accurately indicated the severe damage from the initial displacement while the fatigue model shows no real evidence of this as shown in Figure 2-6., in addition the Park and Ang model also indicated the damage resulting from the two minor tremors. In conclusion Kunnath et al. (1996) summarised that the Park and Ang index consistently provided accurate damage measures at varying limit states and was the most applicable of the non-fatigue models.

2.4 Banon and Veneziano Index

The Banon and Veneziano Index (1982) is based upon a combination of ductility and dissipated energy, and it also incorporates probabilistic concepts. The damage index is made up of the Equations, 2.10, 2.11 and 2.12.

![]() Equation 2.10

Equation 2.10

Where: ![]() Equation 2.11

Equation 2.11

Equation 2.12

Equation 2.12

A normalized value is often used and is obtained by dividing the given expression by the value it assumes at failure in a monotonic test. As with the index proposed by Roufaiel and Meyer, the structure is considered undamaged when the damage index is less than or equal to zero and failure has occurred when the damage index is one.

2.5 Cosenza et al. (1993) Index

This is defined where the displacement ductility value is a measure of the damage parameter and the ultimate value is defined as the ductility obtained under monotonic testing, giving:

Equation 2.13

Equation 2.13

2.6 Bracci et al. Index

The Bracci et al. (1989) index is based on the relation of demand and capacity where the total capacity of the component to sustain damage, is defined as the area between the monotonic load-deformation curve and the fatigue failure envelope. The damage demand consists of strength loss and deformation related damage. Strength loss is defined as the loss of a components ability to sustain damage due to strength degradation and dissipated hysteric energy and deformation damage corresponds to irrecoverable permanent deformations. The damage potential, ![]() , the strength damage,

, the strength damage, ![]() , and the deformation damage,

, and the deformation damage, ![]() , combine to form the damage index defined as:

, combine to form the damage index defined as:

![]() Equation 2.14

Equation 2.14

Using the origin-centred bilinear relationship and assuming that initial and post-yielding stiffness is the same in both directions the following damage index equation was derived by Bracci et al.

![]() Equation 2.15

Equation 2.15

Bracci et al. suggested four classification states based on experimental behaviour and Table 2-2 lists the four damage states.

|

Damage State |

Limiting Damage Index |

|

Serviceable State |

D = 0.33 |

|

Repairable State |

0.33 < D = 0.66 |

|

Irreparable State |

0.66 < D = 1.0 |

|

Collapse State |

D > 1.0 |

Table 2-2 Bracci et al. Damage Classification Levels

2.6.1 Comparison by Liddell (2000)

Liddell also used the Bracci et al. damage index in his research. Liddell concluded that Bracci et al. index gave the best correlation between the calculated index and observed damage along with the Park and Ang (1985) index. Liddell also concluded that in general the Bracci et al index over-predicted the amount of damage that occurred during testing due to the hysteresis model failing to accurately account for pinching in the hysteresis loops and for strength degradation near the conclusion of the tests.

2.6.2 Comparison by Williams and Sexsmith (1995)

Williams and Sexsmith (1995) concluded from their state-of-the-art review that the Bracci et al. index gave a rather more even spread of numerical values across the range of damage states than a lot of the other indices reviewed. The Bracci et al. model appeared to have a stronger theoretical basis and shows a good correlation with observed damage, but could be improved by the implementation of a more sophisticated moment-curvature relationship, rather than the simple bilinear curve currently used.

2.7 Chung, Meyer and Shinozuka Damage Index

In 1987, Chung et al. (1987) proposed a new damage model as a rational measure of damage sustained by reinforced concrete members undergoing strong cyclic loading. The proposed damage index ![]() combines a modified Minor’s hypothesis with damage modifiers that reflect the effect of the loading history, and considers the fact that reinforced concrete members typically respond differently to positive and negative moments:

combines a modified Minor’s hypothesis with damage modifiers that reflect the effect of the loading history, and considers the fact that reinforced concrete members typically respond differently to positive and negative moments:

![]()

Equation 2.16

Equation 2.16

When counting load cycles ni, only those cycles that enter the shaded area shown in Figure 2-7 are considered, i.e., load cycles No. 1 and 2 are not counted when computing the damage index, ![]() .

.

Figure 2-7 Domain for damaging load of positive sense.

The loading history effect is captured by including the damage accelerator aij, which, for positive loading, is defined as:

Equation 2.17

Equation 2.17

where:

Equation 2.18

Equation 2.18

is the stiffness during the j-th cycle up to load level i,

![]() Equation 2.19

Equation 2.19

is the average stiffness during![]() cycles up to load level i, and

cycles up to load level i, and

![]() Equation 2.20

Equation 2.20

is the moment reached after j cycles up to load level i

For negative loading, the damage accelerator is defined similarly,

Equation 2.21

Equation 2.21

Equation 2.22

Equation 2.22

![]() Equation 2.23

Equation 2.23

![]() Equation 2.24

Equation 2.24

Chung et al. have demonstrated the accuracy with which their proposed mathematical model can simulate hysteretic response of reinforced concrete members by numerically reproducing many experimental results. Experimental and analytic load-deformation curves of beams tested by Hwang (1982) and Ma, Bertero, and Popov (1976) are shown in Figures 2-8 and 2-9. Agreement between numerical and experimental results was in general excellent.

Further comparisons were made by Chung et al. (1990) of their damage index using the experimental and numerical values of cumulative dissipated energies of specimens which have been tested by Hwang (1982), Ma, Bertero and Popov (1976) and Popov, Bertero and Krawinkler (1972). Disagreements between experimental and numerical results are most noticeable in the early load cycles of some of the specimens, but the total energies dissipated by the time the tests were terminated show very good agreement. (Chung et al. 1990).

Hatamoto et al. (1990) defined four damage states based on the Chung et al. (1987) damage index. The four damage states considered are: Minor, Repairable, Irreparable and Unsafe. The ranges of the damage index for these four states are presented in Table 2-3.

Figure 2-8 Experimental and analytic load-deformation curves for Beam S2-3 tested by Hwang (1982) (1 in. = 2.54cm; I kip = 4.448 kN)

Figure 2-9 Experimental and analytic load-deformation curves for Beam R5 tested by Ma, Bertero, and Popov (1976) (1 in. = 2.54cm; I kip = 4.448 kN)

|

Damage State |

Range of the damage index |

|

Minor |

0.0 – 0.2 |

|

Repairable |

0.2 – 0.5 |

|

Irrepairable |

0.5 – 1.0 |

|

Structure Unsafe |

= 1.0 |

Table 2-3. Chung Mayer and Shinozuka (1987) damage index for different damage states as defined by Hatamoto et al. (1990)

2.8 Damage index by Kunnath et al. (1992)

Kunnath et al. proposed a damage index that could be used in computational analysis. This superseded the program DRAIN-2D (Kanaan and Powell, 1973) and IDARC (Inelastic Damage Analysis of Reinforced Concrete) (Park and Ang 1985). Their damage index was based on moment, rotation and dissipated hysteretic energy and is shown in Equation 2.25.

![]() Equation 2.25

Equation 2.25

The index was formed to be used in IDARC however it can also be used directly to determine damage at each member cross section. Kunnath et al (1992) stated, “the intent of the ![]() parameter was to provide a correlation between strength loss and damage, the present version uses the same parameter for both damage computations and hysteretic modelling.”

parameter was to provide a correlation between strength loss and damage, the present version uses the same parameter for both damage computations and hysteretic modelling.”

The strength degrading parameter (![]() ) can have varying values as shown in Table 2-4.

) can have varying values as shown in Table 2-4.

|

Description for |

|

|

Well Detailed Section- No Deterioration |

0.05 |

|

Nominal Deterioration |

0.1 |

|

Poorly Detailed Section- Severe Deterioration |

0.4 |

Table 2-4: Typical Range of Values for ß

However ![]() can be calculated using the following formula:

can be calculated using the following formula:

![]() Equation 2.26

Equation 2.26

The effects that ![]() has on the hysteretic curves that it models can be seen in Figure 2-10.

has on the hysteretic curves that it models can be seen in Figure 2-10.

Figure 2-10. Effect of ß on the hysteretic curves (Kunnath et al, 1992)

Stone and Taylor (1993) calibrated the damage index proposed by Kunnath et al (1992) to the damage conditions. They determined after close examination of the data that the tenth percentile of each of the three limiting conditions would provide the threshold for the damage index. From this Stone and Taylor defined the different values that the damage index could return, these are shown in Table 2-5.

|

Damage Condition |

Limiting Damage Index |

|

No Damage |

D < 0.11 |

|

Repairable |

0.11 |

|

Demolish |

0.4 |

|

Collapse |

D |

Table 2-5. Damage Condition and corresponding Limiting Damage Indices (Stone and Taylor, 1993)

3.0 Theory (JB)

This section provides the background theory on concepts that formed the basis of this report. Section 3.1 details the design theory of earthquake reinforced structures in New Zealand. Section 3.2 summarises the principal failure mechanisms of reinforced concrete structures under earthquake loadings. Section 3.3 covers the link between structural damage and observed damage. Section 3.4 summarises the formulae that were utilised for processing data recorded during testing.

3.1 Earthquake Reinforced Concrete Structures

New Zealand lies on the edge of the Pacific Plate and therefore has very active fault lines running through most of the country. Since the 1840’s there have been 17 shallow (within 40km of the surface) earthquakes with a magnitude greater than 7.0 on the Richter scale, including five greater than 7.5 (GeoNet, 2005). Design for earthquake resistance of reinforced concrete structures throughout New Zealand is essential because of the risk posed by large earthquakes. The design of structures for resistance to earthquakes in New Zealand has been an important part of many New Zealand Standard Design Codes including the current NZS 4203:1992 Standard Loadings Code.

3.1.1 Current Performance Criteria

The 1992 New Zealand standard for general structural design and design loadings for buildings (NZS 4203:1992) specified two performance criteria:

1) Serviceability Limit State:

To protect the building during a one in 10 year earthquake from structural damage and to limit damage in non structural components (NZS 4203:1992).

2) Ultimate Limit State:

To protect life and to ensure the building will not collapse in a one in 450 year earthquake (NZS 4203:1992).

3.1.2 Current Design Methodology for Ultimate Limits

To achieve the ultimate limit NZS 4203:1992 specifies the ultimate elastic horizontal inertia force ![]() for different areas of New Zealand. This ultimate elastic horizontal inertia force can be up to 1.0g and therefore the costs involved in constructing a building to withstand ultimate limit make elastic design uneconomic in all but high importance public buildings. For an economic solution to elastic design, the design methodology of ductile building response is used. The ductility of a building is the ability to sustain its force carrying capacity while being displaced in the post-elastic range (Park, 2001). The building must carry a design horizontal inertia force

for different areas of New Zealand. This ultimate elastic horizontal inertia force can be up to 1.0g and therefore the costs involved in constructing a building to withstand ultimate limit make elastic design uneconomic in all but high importance public buildings. For an economic solution to elastic design, the design methodology of ductile building response is used. The ductility of a building is the ability to sustain its force carrying capacity while being displaced in the post-elastic range (Park, 2001). The building must carry a design horizontal inertia force ![]() , specified in NZS 4203:1992, and ductility must be maintained in the post-elastic range up to the ultimate horizontal displacement

, specified in NZS 4203:1992, and ductility must be maintained in the post-elastic range up to the ultimate horizontal displacement ![]() , see Figure 3-1.

, see Figure 3-1.

|

![]()

![]()

Figure 3-1 Ductility Two Response for a building period of greater than 0.7 seconds

Ductility can be achieved by designing plastic hinges into buildings (Figure 3-2). This is a cost effective way of allowing the building to behave in a ductile manner up to ![]() whilst protecting life and ensuring the building will not collapse in a one in 450 year earthquake.

whilst protecting life and ensuring the building will not collapse in a one in 450 year earthquake.

Figure 3-2 Plastic Hinges in a three bay three story building

3.1.3 Pre 1972 Design

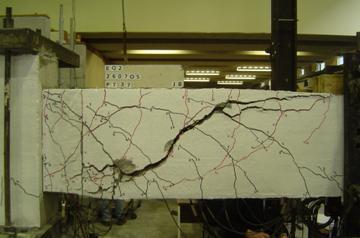

NZS1900 (1965) was the prevalent design code used in New Zealand from 1965 to 1972. It had limitations in that the design earthquake forces ![]() were generally much smaller than those which are now required under NZS4203:1992. Therefore buildings designed to these reduced forces will go further into the post-elastic range during a significant earthquake. For the NZS4203:1992 ultimate limit states to be achieved the building would have to have a larger amount of ductility. Although NZS1900 incorporated the concept of designing for ductility, there was minimal understanding of ductile behaviour during earthquakes. Through our lab testing and other testing, damage in critical sections of buildings has been predicted during earthquakes. Typical predicted failures include beam and beam column joint failure. The beam and beam column joints fail through a number of mechanisms including; longitudinal bars sliding through the joints (Speed, 2005 and Russell, 2005) and not enough shear reinforcement in both the column and the beam (Figure 3-3 and Figure 3-4). During this period the Ministry of Works, which was designing all government owned buildings and the majority of other multi-storey buildings in New Zealand, was using a Code of Practice (P.W. 81/10/1: May 1970) which was a supplement to the NZS1900 design codes. The purpose of this Code of Practise was to minimise non structural damage of government buildings. In this supplement extra emphasis was given to shear reinforcement in the joint zone, however in comparison to modern codes the shear reinforcement was still lacking. In our study we have seen that low amount of shear reinforcement leads to the shear failure of the beam (Figure 3-4).

were generally much smaller than those which are now required under NZS4203:1992. Therefore buildings designed to these reduced forces will go further into the post-elastic range during a significant earthquake. For the NZS4203:1992 ultimate limit states to be achieved the building would have to have a larger amount of ductility. Although NZS1900 incorporated the concept of designing for ductility, there was minimal understanding of ductile behaviour during earthquakes. Through our lab testing and other testing, damage in critical sections of buildings has been predicted during earthquakes. Typical predicted failures include beam and beam column joint failure. The beam and beam column joints fail through a number of mechanisms including; longitudinal bars sliding through the joints (Speed, 2005 and Russell, 2005) and not enough shear reinforcement in both the column and the beam (Figure 3-3 and Figure 3-4). During this period the Ministry of Works, which was designing all government owned buildings and the majority of other multi-storey buildings in New Zealand, was using a Code of Practice (P.W. 81/10/1: May 1970) which was a supplement to the NZS1900 design codes. The purpose of this Code of Practise was to minimise non structural damage of government buildings. In this supplement extra emphasis was given to shear reinforcement in the joint zone, however in comparison to modern codes the shear reinforcement was still lacking. In our study we have seen that low amount of shear reinforcement leads to the shear failure of the beam (Figure 3-4).

|

Figure 3-3 Shear failure of the beam column joint after the California Earthquake

Figure 3-4 Shear Failure of a beam in laboratory testing

3.2 Failure Mechanisms

There are three main failure mechanisms for reinforced concrete members. They are shear, flexure and low cycle fatigue. As discussed in Sections 3.2.1-3.2.3 below.

3.2.1 Shear

Gosain et al (1977) noted that when reinforced concrete members were subjected to repeated and reversed loads that produced large deflections, the shear failure of the member may limit the ductility of the member.

There are two main modes of shear failure. The first is the confining shear reinforcement failing. Typical of confining shear reinforcement failure are large diagonal shear cracks which can be seen in Figure 3.4. The second is the diagonal concrete compression strut failing. This results from too much confining shear reinforcement and leads to an undesirable brittle failure.

3.2.2 Flexure

Reinforced concrete can fail in flexure in either compression or tension. Compression failure occurs when the ratio of steel to concrete is too high and the concrete develops yield strain before the steel does. Only small cracks and deformations are observed before a brittle failure occurs, and consequently this is undesirable in concrete structures. Tensile failure occurs when the yield strain of the steel is reached before that of the concrete. Large cracks and deformations are observed as the member fails in a ductile manner.

3.2.3 Low Cycle Fatigue

Kunnath et al (1997) observed the low cycle fatigue of longitudinal bars in columns when large displacement amplitudes were applied to test specimens. They found that testing that was predominantly inelastic would be more likely to have the longitudinal bars fail.

3.3 Measuring Observed Structural Damage

There is little information available on how to measure the structural damage of reinforced concrete beams designed to pre 1972 design codes after a seismic event. The state of damage of a reinforced concrete beam could be predicted by using damage indices prior to or after a seismic event (Section 2). To measure the observed structural damage of a reinforced concrete beam it is necessary to be able to compare known observed damage with a state of calculated damage. Many damage conditions have been proposed including Park and Ang (1985) and Stone and Taylor (1993). They have attempted to correlate damage indices with observed damage. However these damage conditions are not rigorously defined and therefore it is not clear by observation what state of damage a reinforced concrete beam is in. For accurate prediction of damage to reinforced concrete beams designed to pre 1972 codes it is necessary to correlate observed damage from laboratory testing with a state of damage. This state of damage should be obtained from a damage index to also allow prediction of damage during a seismic event.

3.4 Processing Data

Changes in length of our beam, were taken from the network of the displacement transducers, as a gauge group, as detailed in Section 4.4, during testing. By processing these changes we were able to calculate the various components of displacement, curvature, beam depth increase and elongation as the test proceeded.

3.4.1 Components of Displacement

When force is applied by an actuator to a reinforced concrete beam, we can measure the displacement of the beam at the point where the actuator is. This displacement can also be approximated by combining the individual components of this displacement. In our testing, Shear, Flexure and Rocking all contributed to the displacement which we measured and these can be calculated as below.

3.4.1.1 Shear Displacement

Shear displacement can be found using the change in diagonal lengths of a gauge group, as shown in Figure 4-14, and the distance between the centre of this gauge group and the centre of the actuator (![]() ). Figure 3-6 below shows the shear displacement component.

). Figure 3-6 below shows the shear displacement component.

Figure 3-6 Shear Displacement

Solving for the width of a gauge group (![]() ):

):

![]() Equation 3.1

Equation 3.1

![]() Equation 3.2

Equation 3.2

Equating ![]() and solving for the shear displacement of the gauge group (

and solving for the shear displacement of the gauge group (![]() ):

):

![]() Equation 3.3

Equation 3.3

The ![]() factor is nominally small for beams that do not have a large amount of shear deformation such as beams designed to modern codes, and therefore this has been excluded in other testing (Lau 2001). However because our beams have shown large amounts of shear deflection these numbers are more significant and therefore they have been included in our calculations.

factor is nominally small for beams that do not have a large amount of shear deformation such as beams designed to modern codes, and therefore this has been excluded in other testing (Lau 2001). However because our beams have shown large amounts of shear deflection these numbers are more significant and therefore they have been included in our calculations.

The total shear deflection can be found by adding together all of the gauge group displacements:

![]() Equation 3.4

Equation 3.4

3.4.1.2 Flexural Displacement

Flexural displacement at the actuator can be calculated by finding the angle of rotation within a gauge group (![]() ) and multiplying this angle by the distance between the centre of this gauge group and the centre of the actuator (

) and multiplying this angle by the distance between the centre of this gauge group and the centre of the actuator (![]() ). Figure 3-7 below shows the flexural displacement component.

). Figure 3-7 below shows the flexural displacement component.

Figure 3-7 Flexural displacement

Rotation within a gauge group (![]() ):

):

![]() Equation 3.5

Equation 3.5

Flexural displacement at the actuator:

![]() Equation 3.6

Equation 3.6

The total flexural displacement can be found by adding together all of the gauge group displacements:

![]() Equation 3.7

Equation 3.7

3.4.1.3 Rocking Displacement

Elongation of the tensioning down rods (see Figure 4-11) causes the test unit to rock. Movement at the column faces can be measured (![]() and

and ![]() ) and this by multiplying by the distance to the actuator

) and this by multiplying by the distance to the actuator ![]() , displacements due to rocking can be measured. Figure 3-8 below shows the displacement component as a result of rocking.

, displacements due to rocking can be measured. Figure 3-8 below shows the displacement component as a result of rocking.

Figure 3-8. Rocking Displacement

Rocking displacement at the actuator:

![]() Equation 3.8

Equation 3.8

3.4.1.4 Calculated Displacement

This can be found be adding Shear, Flexure and Rocking Displacement together:

![]() Equation 3.9

Equation 3.9

3.4.2 Curvature

Curvature is the rate of rotation of a section of the beam. It is used in the determination of some damage indices. It can be calculated for each gauge group and is found by dividing rotation (![]() ) by the width of the gauge group (

) by the width of the gauge group (![]() ).

).

Rotation within group (![]() ):

):

Equation 3.10

Equation 3.10

Curvature within the group:

![]() Equation 3.11

Equation 3.11

3.4.3 Elongation

The elongation is calculated to show the change in length of the beam. When the beam increases in length this can cause displacement of the adjacent columns and additional buckling of the beam itself. The elongation of each panel itself is calculated using the displacement readings taken from each of the gauge groups by taking the sum of the changes in length of the top and bottom chords, dT and dB respectively. This represented diagrammatically below in Figure 3-9.

Figure 3-9 Elongation of a panel

Hence the elongation within a panel is given by:

![]() Equation 3.12

Equation 3.12

Finally the Total Elongation of the beam is comprised of the summation of the elongations of all the separate panels:

![]() Equation 3.13

Equation 3.13

3.4.4 Increase in Depth

The increase in depth of the beam can be measured directly by the increase in length of the displacement transducers. It is useful for showing the correlation between shear deformation and actuator displacement. For the gauge group, increase in depth is the average of ![]() and

and![]() . Figure 3-10 below shows the increase in depth of a panel.

. Figure 3-10 below shows the increase in depth of a panel.

Figure 3-10 Increase in depth of a panel

Thus the increase in depth of a gauge group or panel is given by:

![]() Equation 3.14

Equation 3.14

4.0 Test Assembly Design, Construction, and Set-Up (BD)

The testing set-up detailed in this section features a test unit, consisting of two reinforced concrete beams connected by a central column section, mounted onto a concrete testing pedestal. The loading histories applied to the test unit are aimed at simulating the response of the beam section of a reinforced concrete frame structure when subjected to seismic load reversals. Such a structure was selected because similar frames were prevalent in Government Buildings constructed in New Zealand throughout the 1970s.

This formed the basis for the prototype design building, detailed in Section 4.1, that the design of the test units was based on. The actual design of the test specimens themselves however was undertaken using the guidelines laid down in NZS1900 (1965) and the 1970 Ministry of Works Design Codes, and is covered in Section 4.2. Section 4.3 depicts the details of and procedures followed during the construction sequence of the test units. Section 4.4 illustrates pre-testing arrangement of the units and Section 4.5 presents the layout of the instrumentation used during testing. Finally, Section 4.6 describes the manner in which the data gathered using the instrumentation detailed in Section 4.5 was used to isolate the separate displacement components and moment-curvature relationships presented within the data.

4.1 Prototype Design

As previously stated in the introductory Section 4.0 the prototype design building utilised, was based on a government style office building designed and constructed using the prevalent standards from the early 1970s. The project supervisor Dr. Barry Davidson was able to design a three storey, three bay structure that was suitable for the above requirements, which is shown in Figure 4-1.

Using nonlinear time history analyses of two dimensional frame structures five earthquake loading histories were derived, the details of which are covered latter in Section 5.0. When conducting the analysis of the structure the columns were assumed to be pinned at the base and to remain elastic throughout while the beams were identical to those used in the test units, the design of which is covered in Section 4.2. Several key properties used in the above calculations are detailed below;

E = 3E7 kN/m2

Ibeam = 0.000369 m4

Icolumn = 0.0005 m4

Acolumn = 0.09 m2

In order to achieve satisfactory displacement demands on the beams for the separate earthquake loading histories the mass of each floor level was adjusted accordingly.

4.2 Test Unit Design

The design standards implemented during the test unit design are detailed in Section 4.2.1 while the specific details of the beam and column sections are illustrated in Section 4.2.2 and Section 4.2.3 respectively.

4.2.1 Design/Loadings Codes

As noted in the above sections all attempts were made to ensure that the beams being tested were in fact accurate replications of government buildings constructed during the 1970’s. In order to achieve this, the design of the test units specified hereafter is based on the 1970 Ministry of Works Code of Practice for the design of Public Buildings used in conjunction with NZS1900:1965.

4.2.2 Beam Design

It should first be noted that the overall dimensions of the test unit were largely governed by the existing boxing that was available for use in the University Laboratory. This constraint required the adaptation of the overall beam sectional dimensions of the beam to be 200x450. The adopted beam length of 1.55m from the column face was less restricted, as stop ends could be freely placed in the boxing to create a beam of desired length. In addition to the limitations enforced by the boxing the final specified test unit design varied from that of a similar 1970’s structure by the fact that the common concrete and reinforcement strengths of that period being 25MPa and 250MPa respectively, are no longer readily available. Hence a concrete strength of 30MPa and steel reinforcement strength 300MPa were adopted as alternatives.

Working within the above mentioned parameters the resultant reinforcement details as shown in Figure 4-2 and Figure 4-3 were adopted.

Figure 4-2 Reinforcement Layout in Test Unit.

Figure 4-3 Cross Sectional View of Reinforcement Layout.

4.2.2.1 Longitudinal Reinforcement

Using the details provided above in Figure 4.2 and Figure 4.3 the strength provided by the 5-D20H longitudinal reinforcement bars was calculated as per the following:

Tension force in reinforcement;

Equation 4.1

= 471.3 kN

Following on from this the depth of the equivalent rectangular stress was found to be;

Equation 4.2

= 92.4 mm

Therefore;

Equation 4.3

= 345.8 mm

Hence the nominal moment capacity was determined to be;

Equation 4.4

= 163 kNm

From this the nominal flexural strength of the beam was found to be;

Equation 4.5

= 105 kN

4.2.2.3 Transverse Reinforcement

After the completion of the longitudinal reinforcement capacity design the transverse reinforcement capacity of the R6 stirrups at 195 centres was determined.

The shear stress in the concrete;

Equation 4.6

= 1.48 MPa

The requirements specified in NZS1900 governed the chosen ratio of tension reinforcement, which in turn largely dictated the size and number of the longitudinal bars. Hence pw was taken as;

Equation 4.7

= 0.02

Shear strength provide by the concrete;

Equation 4.8

= 116.0 kN

Shear strength provide by the transverse reinforcement;

Equation 4.9

= 33.9 kN

Hence the nominal shear strength was determined to be;

Equation 4.10

= 149.9 kN

It was desired with our initial design as per NZS1900 to have a nominal moment to shear ratio, Mn/Vn, of approximately 1.5. This however was unattainable due to the limitations imposed by the boxing dimensions, and hence an actual ratio of 1.09 was adopted.

4.2.3 Column Design

This was not specifically designed for as the test unit was designed for failure to occur in the beam section, away from the column face. Hence an exact design was not undertaken, and the strength of the column was section was increased to such a level as avoid the possibility of failure occurring in such a manner. The magnitude of this strength increase was taken from a previous test design, outlined in Liddell (2000), which used a similar beam cross-section, and under similar loading histories it was demonstrated that no failure was present in the column section. Hence a similar reinforcement pattern, which consisted of the welding of additional longitudinal reinforcement to the existing bars through the column section as shown in Figure 4-4 was adopted in the design. The full reinforcement details for the beam and column sections can be seen in Figure 4-2 and Figure 4-3.

4.3 Construction Details

In order to conduct an accurate and fair comparison of the chosen damage indices under the influence of the different applied loading histories it was necessary to construct six nominally identical test units. Section 4.3.1 covers the steps taken to minimise the variability of the materials used during construction and Section 4.3.2 details the construction sequence for each of the test units.

4.3.1 Materials:

As previously mentioned each test unit was comprised of two identical reinforced concrete beams extending from either side a of central column section. A summary of the material properties of the reinforcing steel and concrete used in construction of the test units are given in Sections 4.3.1.1 and 4.3.1.2 respectively.

4.3.1.1 Steel Reinforcement

By ensuring that all of the reinforcement steel came from the same production batch the likely hood of any difference in the material properties of individual bars was greatly reduced. The stress-strain curves of four randomly selected sample specimens of the D20H longitudinal reinforcing steel under increasing tensile loading until necking in a 1000 kN Avery test machine can be seen in Figure 4-5.

From these curves it can be seen that although there are some small variations in the ultimate strain value and strain hardening behaviour the yield strength and Young’s modulus remain approximately constant for all of the test samples. Average values of the yield strength and Young’s modulus were calculated from the test data and returned values of 316.75 MPa and 196.35 GPa respectively. The value of yield strength was as expected, being slightly in excess of the specified strength of 300 MPa, while the Young’s modulus was also very close to the conventional grade 300 steel modulus value of 200 GPa.

The longitudinal reinforcing steel that was used in the design and construction of the test units was all Grade 300 deformed bar and was not of the same specifications as the actual reinforcement used in New Zealand Government buildings constructed throughout the 1970s, however this was what was available from the supplier and hence what was used. In order to exactly replicate the beams from such structures it would have be necessary use Grade 250 round bars which are no longer commercially produced in New Zealand.

4.3.1.2 Concrete

The design mix had a specified slump of 120mm and an average compressive strength of 30MPa after 28 days of curing under normal conditions. As mentioned above in Section 4.4.1.1 the materials that were desired for the test units and those that were used were not always of the same specifications. These mix design parameters used were not perfect for the design as ideally 25MPa strength concrete would have been used, as was commonly used in New Zealand throughout the 1970s, but as this was not readily available from the supplier 30MPa strength was used as an alternative.

In order to accurately compare the different loading histories it was important to minimise any variations in the concrete strength between the separate test units. It was identified that possible reasons for inconsistencies in the concrete strength could be attributed to the concrete being sourced from dissimilar batch mixes and being of different curing ages. The concrete samples were tested at the same time as the testing of the corresponding test units. This was done to ensure that the actual concrete strength at the time of testing was known. Figure 4-6 (a) and Figure 4-6 (b) show the concrete strength development history for the two samples, and it can be seen that throughout the duration of the testing process the concrete strength remained relatively constant. From the afore mentioned figures it can be seen that the testing of the beams was undertaken over a period of approximately 60 days, from 30-90 days after pouring, it can also be seen that over this period there was only a small increase in the concrete strength. Due to the insignificance of this change in strength the influence it had on our test results was deemed to be negligible.

Due to constraints imposed by the quantity of available timber boxing it was not possible to pour all of the test unit from the same production batch and therefore two separate pours had to be made each consisting of three test units each. Although the mix design specifications were very similar for both of the pours it can be seen in Figure 4-6 (a) and Figure 4-6 (b) that the development of the concrete strength over time was not the same for both batches.

It was discovered that the exact specifications for each of the concrete mix designs used for construction were not in fact identical as first assumed, the details of the two batches are summarised below in Table 4-1 and Table 4-2. This discrepancy was however deemed to be of negligible significance as the net effect of the difference in compressive strengths from the two separate batches was that the neutral axis of the beam moved by less than 2mm. Thus having a minimal influence on overall strength of the beam.

Figure 4-6 (a) Concrete Strength History Batch Two.

|

Mix Type |

301 |

|

Mix Strength |

30 MPa 13mm |

|

Cement Milburn GP |

310 kg/m3 |

|

Free Water |

173 Litres/m3 |

|

13 mm (SSD) |

1000 kg/m3 |

|

7 mm (SSD) |

610 kg/m3 |

|

Sand (SSD) |

410 kg/m3 |

|

Water Reducer |

400 mL/100 kg of cement |

Table 4-1 Concrete Mix Design for batch one.

|

Mix Type |

301GP |

|

Mix Strength |

30 MPa 13mm |

|

Cement Milburn GP |

340 kg/m3 |

|

Free Water |

210 Litres/m3 |

|

13 mm (SSD) |

580 kg/m3 |

|

7 mm (SSD) |

800 kg/m3 |

|

Sand (SSD) |

540 kg/m3 |

|

Water Reducer |

400 mL/100 kg of cement |

Table 4-2 Concrete Mix Design for batch two.

The strength characteristics of the initial batch shown in Figure 4-6 (a) demonstrates an actual average strength of 32.6MPa which is higher than that of the second batch, Figure 4-6 (b), which had an actual average strength of 27.7MPa, which is below the specified strength of 30MPa. This lack of compressive strength was deemed to be attributable to there being additional free water being added to the mix prior to pouring and not the difference in the mix designs. Slump tests performed in the University Laboratory during the pouring of the test units, as illustrated in Figure 4-7, showed that the actual slump of the first batch was 150mm and the second batch was 190mm. Both in excess of the specified slump of 120mm.

Figure 4-7 Concrete slump Test.

At the time of the pouring and the slump tests 18 sample concrete test cylinders were prepared, nine for each of the batches poured which correlated to three for each of the test units. These test cylinders were prepared and tested in accordance to New Zealand Standard Methods to Test for Concrete NZ 3112 Part 2 1986.

4.3.2 Construction Sequence

All of the construction and assembly of the test units took place in the University test Laboratory and began with the tying of the steel reinforcing cages. This process was undertaken in three main steps; firstly the central column section was assembled and through this the longitudinal D20H bars were inserted into their approximate locations. The overhead crane was then used to raise this sub-assembly into a position where the transverse reinforcement could be tied into position.

Following on from the completion of the reinforcement cages the required timber boxing was constructed. As stated in Section 4.2 the dimensions of the test units was largely governed by the existing boxing that was available in the laboratory. This meant that all that was required for the assembly of the boxing was the screwing together of the already pre-cut components, using 45mm zinc chromate countersunk screws at 500mm centres, and coating the interior with oil to assist with the removal of boxing once the concrete had sufficiently hardened. The boxing itself consisted of 75 x 50 framing timber and 20mm thick particle board and possessed sufficient strength as to ensure that deflections during the pouring of the concrete were negligible.

Figure 4-8 Pouring Concrete.

Figure 4-10 Concrete Placement and Finishing.

Using the overhead crane the reinforcement cages where positioned within the boxing and the concrete poured, once again by means of overhead crane and a large steel bucket, as illustrated in Figure 4-8. After vibrating the concrete to ensure that any air voids were removed and completing the concrete finishing work with hand screeds, Figure 4-9, the test units were covered with wet hessian, to reduce cracking, and left to cure.

4.4 Test Arrangement

Figures 4-11 and 4-12 detail the set-up arrangement that was used during the testing of the twelve beams. The test unit was placed symmetrically onto the concrete testing pedestal prior to testing using the overhead crane. Six stressing rods that passed up through the core of the pedestal and the outside of the central column section were used to tension down the test unit to the strong floor. The upper ends of the stress rods were fed through a 100mm thick RHS steel plate that was mortared into position onto the top of the column section, the rods were then each loaded to 245kN. By stressing down the test unit and restraining it into position any structural deformation that may have occurred due to fixed body rotation of the entire test unit was minimised. Although it should be noted that a small amount of rocking displacement did occur due to the elongation of the tensioning rods, this is detailed in Appendix A.

The chosen loading histories were applied to each of the beams using an actuator located at a distance of 1.55m from the column face and mortared into position, as can be seen in Figure 4-11. This distance is equal to half of the clear distance between column faces from the chosen design proto-type building structure, in order to simulate the ultimate deflection of the beam at mid-span. In the push direction the actuator had a load capacity of 490 kN and in the pull direction its capacity was 245 kN. Taking into consideration the fact that ten of the twelve loading histories involved in the testing schedule used cyclic load reversals, it was recognised that the lower of these two capacities, the pull direction, could possible limit the flexural strength of the beams. A check was made to ensure that the maximum probable demand placed upon the actuator during the application of the loading histories was below that of the lower capacity of 245 kN.

An overstrength factor of 1.3 was used to gain an estimate of the maximum probable demand to be;

which is well below the lower capacity of the actuator.

From Figure 4-11 it can be seen that the end of the test unit not connected to the actuator (hydraulic jack) was left completely unsupported. This was done in an effort to minimise the influence of force and strain transfer from the beam that was being tested into the second unsupported beam. To eliminate any tensional rotation of the beam being tested a steel bracing system was attached to the beam end as illustrated in Figure 4-12.

4.5 Instrumentation

During the construction of the test units, after the tying of the cages and prior to the pouring of the concrete, steel lugs were welded onto the longitudinal reinforcement at the locations detailed in Figure 4-13. The length of these lugs was sufficient to extend from the reinforcing steel out to surface of the concrete. Before the concrete was poured grease tape was wrapped around the lugs and length of plastic tubing inserted over the lug and grease tape. When sufficient time had passed for the concrete to cure the plastic tubing and grease tape was remove from the lugs to allow adequate clearance between the lug and the concrete cover. At the points where the lugs emerged from the concrete a network of displacement transducers (portal gauges); refer Figure 4-14, was attached to the beam face to measure relative displacements during the testing of the beam, as shown in Figure 4-13. The displacement readings taken from the transducers were collated using an HP data logger, which in turn allowed the calculation of the various displacement components; flexural, shear, and rocking as well as the reinforcement strains throughout the duration of the testing process, as detailed in Section 3.4. The displacement

Figure 4-13 Instrumentation Layout

Three separate methods were used to measure and record the deflection of the free end of the beam, this was done in an effort to confirm the readings gained and to eliminate any uncertainties. The measurements were taken from the displacement reading from the actuator, a linear variable deflection transformer (LVDT) or turnpot, and manually through a steel rule connected to the end of the beam.

4.6 Separate Displacement Components

It was briefly noted above in Section 4.5 and covered in more detail in Section 3.4 that the displacement induced by the loading of the actuator was comprised of three separate components, these being; flexure displacement, shear displacement, and rocking displacement. By analysing the deformation data taken from the displacement transducer network and stored in the data logger these different components were able to be isolated

5.0 Applied Loading Histories (JS)